Frequently Asked Questions About Carbon Offsets

July 10, 2019

Frequently Asked

Questions About

Carbon Offsets

Welcome to our Frequently Asked Questions page about using a carbon footprint calculator and carbon offsets!

Here, we aim to address common queries regarding carbon offsetting, a crucial tool in combating climate change. Whether you’re new to the concept or looking to deepen your understanding, this guide is designed to provide clarity on how carbon offsets work, their impact, and how they can be utilized to reduce your carbon footprint. If you’ve used a carbon footprint calculator and are wondering how to offset your carbon footprint, you’ve come to the right place. Read on to explore answers to the most pressing questions surrounding carbon offsets.

1. What are carbon offsets?

We all produce carbon as a result of using fossil fuels directly, or indirectly when we use products that were produced using fossil fuels. For example, we directly produce carbon when we drive a car or take a flight. When you eat food that has been produced with artificial fertilizers and pesticides (which are made from oil) you are indirectly producing carbon. The amount of carbon you produce is your “carbon footprint.” On average, each US consumer produces about 26 tons of carbon dioxide per year. (That’s 7 tons of carbon.)

Carbon offsets are a way to compensate for carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by funding projects that reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere. An offset works by engaging in an activity that does the opposite. Instead of producing carbon, you do something to absorb carbon.

Luckily, plants are very good at this. Whenever you plant something, the plant will be absorbing carbon that would otherwise remain in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming.

Professor Pimm, Saving Nature’s Founder and President, likes to lead an exemplary, energy efficient life, except he flies a hundred thousand miles a year or more. So, using our carbon calculator for flight emissions, he determines how many tree to plant to offset his carbon emissions from flying. For example, a return flight to Rio de Janeiro puts about 1 ton of carbon dioxide into the air, per person. That’s about $4 worth — much less than a week’s supply of the coffee he drinks. (Biodiversity friendly, fair trade, organic, of course.)

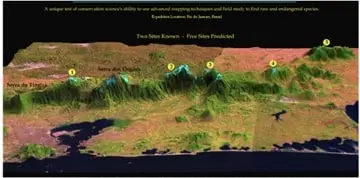

Louie Psihoyos, Oscar-winning director, asked Pimm to be in his documentary Racing Extinction. Pimm’s condition was that there would be a donation to offset the film’s carbon emissions. Psihoyos and his team made a very detailed calculation. It came to close to what Pimm had suggested on the simple basis of how many people worked for how many months and how many flights they took. After all that, Psihoyos felt that the donation was so small, he gave several times the calculated amount, for which we were very grateful. If you wait until the very end of the documentary, you will see it paid for trees planted at Jama Coaque, Ecuador.

2. How do carbon offsets help reduce emissions?

By investing in carbon offset projects, individuals and organizations can effectively counterbalance their own carbon emissions. For example, if you take a flight and calculate your carbon footprint using a carbon footprint calculator, you can then purchase carbon offsets to “offset” the emissions from your flight.

3. How do I offset my carbon footprint?

To offset your carbon footprint, you can calculate the emissions from your activities using a carbon footprint calculator and then purchase carbon offsets from reputable providers. These offsets fund projects that reduce or remove an equivalent amount of CO2 from the atmosphere.

4. Should I use a carbon footprint calculator to work out my annual carbon emissions?

Carbon calculators are a great way to estimate your annual carbon emissions. Our carbon footprint calculator is based on the EPA estimates for carbon emissions. We also help determine how many trees to plant to offset your carbon footprint with a donation to Saving Nature.

Check our our carbon footprint calculator.

5. How does donating to Saving Nature offset my carbon footprint?

At Saving Nature, we’re keen to slow the extinction rate and, in the process, we plant a lot of trees that offset carbon emissions. When you donate to Saving Nature, we channel funds to turn degraded cattle pastures into forests. As the forests regrow on the land we help acquire, they sequester about 26 tons of carbon dioxide (7 tons of carbon) per hectare per year. This sequestration rate continues for about 20 years, then continues, but at a slower rate.

Therefore, over 20 years,we estimate that each hectare we acquire sequesters at least 540 tons of carbon dioxide (140 tons of carbon). We make deals to purchase and restore land at under $2,000 per hectare, so we are recovering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere at about $4 per ton. (Most of our deals are much cheaper than that. For the ones that are more expensive, we seek help from foundations).

6. Is Saving Nature’s carbon certified?

This is the question we get most from companies. There are certified carbon offsets and that allows them to be traded. Now, certification is a good idea. It creates a product that companies can trade because everyone trusts those who do the certification. We are working to certify our carbon credits in Colombia.

7. What are the scientific facts about global warming?

First, the emissions. Global carbon emissions are about 10 billion tons of carbon per year. That goes into the atmosphere as 37 billion tons of carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas. That’s about 1.5 tons of carbon (5.5 tons of carbon dioxide), per person per year, but rich countries emit far more than poor ones.

Deforestation — of which the burning of tropical forests is the major component —contributes about 10% of those emissions. Some tropical countries have much higher carbon emissions than one might expect from their industrial activities.

8. How much carbon is there in forests and how much do forests sequester when we replant them?

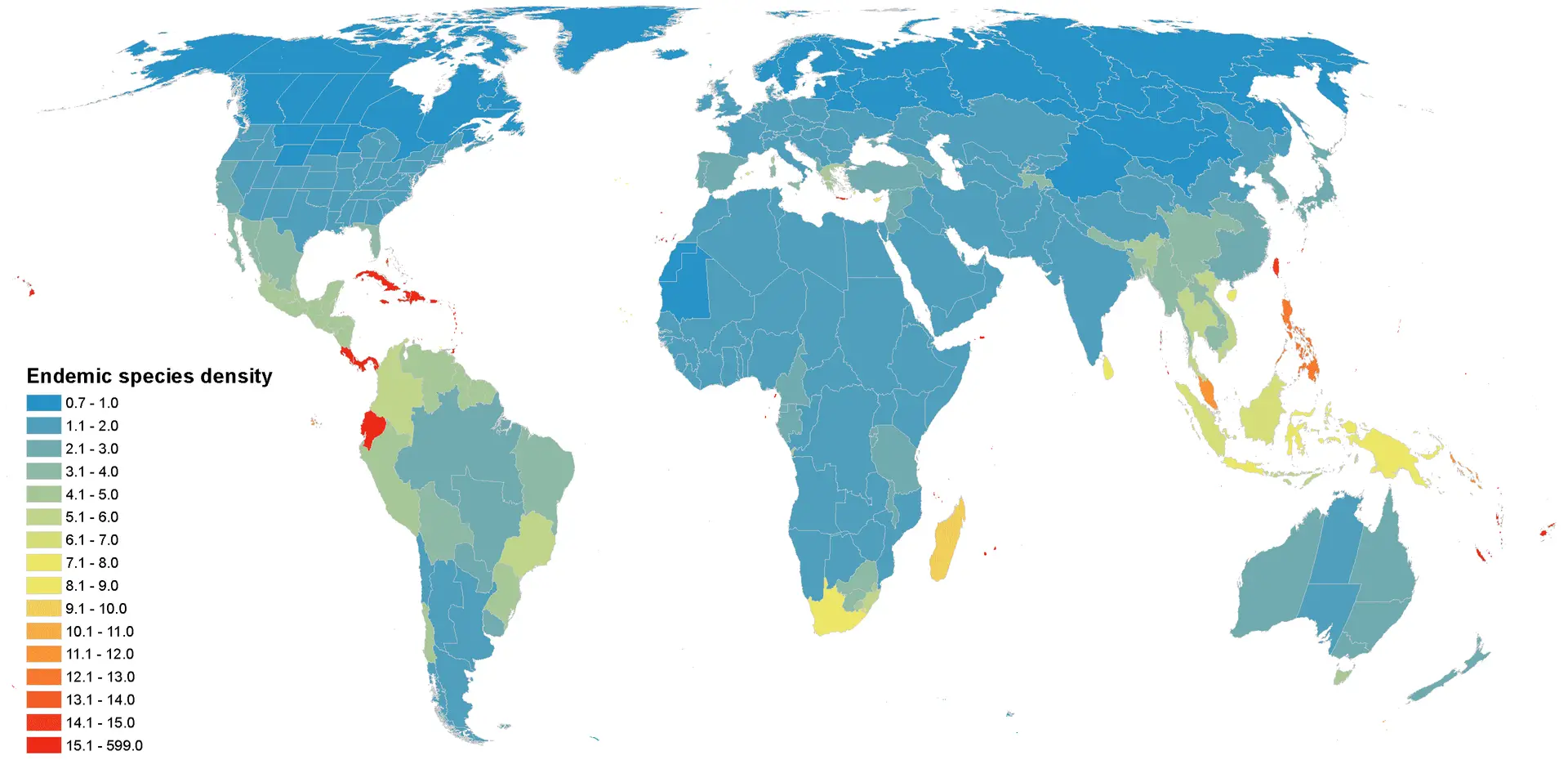

A recent study by Saatchi et al. maps current estimates of how much biomass there is in forests.The units on the map are in megagrams, which is a ton — and the measure is of biomass. About half of biomass is carbon. In most of the places where Saving Nature restores forests, there’s a minimum of 300 tons of biomass or 150 tons of carbon per hectare.

These are the areas shown in orange or red. (One Saving Nature site is in dry forest and the amount is less.) A variety of other papers show averages above 200 tons of carbon per hectare, especially in the wettest forests. As luck would have it, there is a detailed study done, in part, at one of the key Saving Nature sites: La Mesenia in Colombia. (Not luck, really: when one protects forests, one provides a place for scientists to work!) Gilroy et al. show that the primary forest there had 200 tons of carbon per hectare.

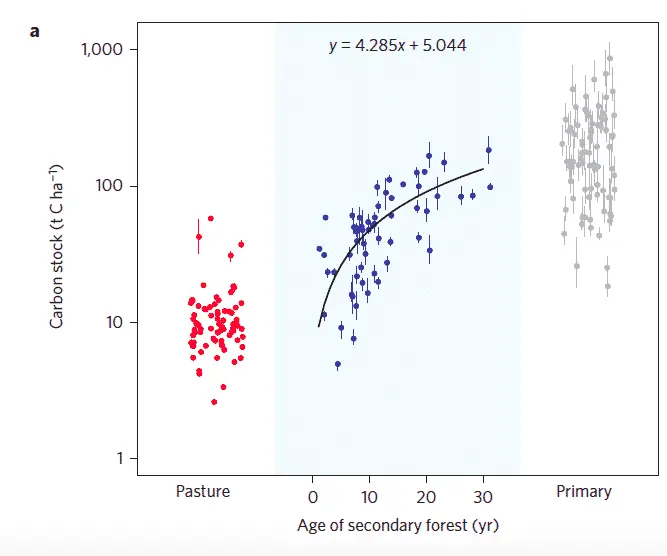

This study also shows something else. The forests go from about 10 tons of carbon per hectare as pastures to about 100 tons in about twenty years — so an average of about 4.5 tons per year, but higher in the first decade than the second. It’s much harder to study the change in forest biomass than just the biomass — one needs several measurements, of course.

So, our land purchases are indeed the gift that keeps giving and giving. In our calculations, we’ve used a higher annual rate of carbon sequestration, but a much shorter period over which the carbon accumulates.

9. Can you explain carbon math?

Well, yes, if you insist. The bad news is that different publications use different units. We use metric tons of carbon. Some publications talk about carbon, some about carbon dioxide, and some don’t tell you which. A ton of carbon becomes 3.67 tons of carbon dioxide when you burn it. (That’s because the molecular weight of carbon is 12 and carbon dioxide is 44: 44/12 = 3.67.) And some studies use biomass. About half the biomass of wood is carbon.

We use hectares, 100 metres by 100 metres, and 1 hectare is roughly 2.5 acres. There are 100 hectares to a square kilometre. Some publications use hectares, some square kilometres, but worst of all, the Food and Agriculture organisation uses 1,000 hectares — or 10 square kilometres.

As if this wasn’t bad enough! Some studies use tons, while others use megagrams. A megagram is, well, a ton. And after all that you will be relieved to know that one Imperial ton is almost the same as a metric done (1 ton = 1.02 metric tons). We’re using metric tons. The worst news of all is that many studies don’t say what they are using! (It can take an age to find out what they actually mean.)

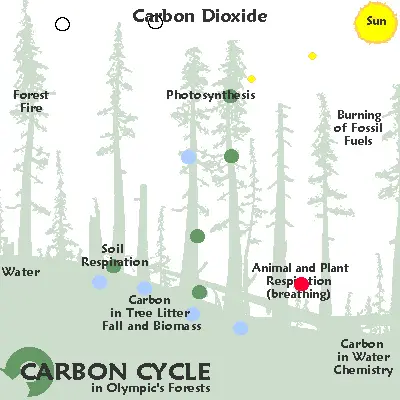

10. How can I teach the carbon cycle to high school students?

Teaching children about the carbon cycle doesn’t have to be confusing. Once they understand the relationship between trees and climate change, they can be climate change ambassadors to friends and family.

Contact Professor Pimm for details of his presentation to High Schools on how to estimate how much carbon there is in a forest.

11. What can I do to fight climate change?

Calculating and offsetting your carbon footprint by planting trees to restore rainforests is a great way to take personal responsibility climate change. The next step is knowing how many trees to plant to offset your carbon footprint. Our carbon footprint calculator will help you do both.

Donating to Saving Nature to plant trees to offset carbon dioxide and rescue biodiversity solves the two most pressing environmental problems the world faces—mass species extinction and deforestation—at the same time! We will continue to use both science and savvy to connect, protect, and restore forest corridors. We invite you to join us in this ambitious effort!

Please support forest restoration and connectivity, and share our hope for the future of species struggling for survival in the face of global warming!

Footnotes

FIGURE 1: Map of carbon in tropical forests: from Saatchi SS, Harris NL, Brown S, Lefsky M, Mitchard ET, Salas W, Zutta BR, Buermann W, Lewis SL, Hagen S, Petrova S. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011 Jun 14;108(24):9899-904. 3.

FIGURE 2: Accumulation of carbon in regenerating tropical forests. From Gilroy JJ, Woodcock P, Edwards FA, Wheeler C, Baptiste BL, Uribe CA, Haugaasen T, Edwards DP. Cheap carbon and biodiversity cobenefits from forest regeneration in a hotspot of endemism. Nature Climate Change. 2014 Jun;4(6):503.