January 14, 2019: Stuart Pimm sat down with Ella Barnett to reflect on the Tyler Prize and its role in his conservation vision for SavingSpecies.

He has since launched Saving Nature in July 2019 as the successor to SavingSpecies. His new organization reflects his now broader vision for working toward a sustainable future to solidify and amplify the gains achieved. Saving Nature has recruited an expanded team of leading conservation professionals to help shape the strategic direction for saving vanishing ecosystems, preventing extinctions, and improving the lives of communities most impacted by environmental degradation.

Dr. Stuart Pimm, the Doris Duke Chair of Conservation Ecology at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, is a founding father of modern conservation. A trained biologist and theoretical ecologist, he has used his multidisciplinary background in the application of understanding biological conservation. It is because of him that science was implemented into conservation and species population, and extinction rates started to be tracked. In 2010, Pimm was awarded the Tyler Prize for his extraordinary contribution to the environment. Now, eight years on, the Tyler Prize sat down with him to find out what Pimm has been working on since. Unsurprisingly, his unfailing dedication towards the environment in general – and conservation in particular – has crafted a path towards a rapidly expanding non-profit organisation that aims to restore international species populations while working at a local level.

How did the Tyler Prize help you to contribute to the environment?

I was incredibly fortunate to get the Tyler Prize, and I felt that one of the things that I could do with that money was to use it to create an organization, SavingSpecies. It’s an organization to try and look at what are the key places around the world that we need to protect if we’re going to save biological diversity, biodiversity. The money I received from the Tyler Prize has certainly helped me push that agenda.

What does SavingSpecies do?

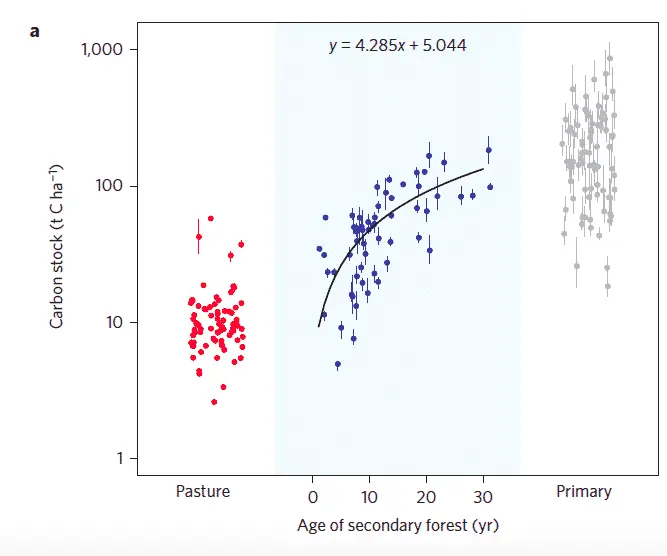

SavingSpecies, identifies the critical parts of the world where species are going extinct, through finding local partners. We want to empower local conservation groups, and we help them raise money to do restoration of habitats, typically forest restoration.

We solicit proposals from people in developing countries that want to manage their land by reconnecting these fragmented landscapes. We get proposals from people, and then we try to raise the money from donors, and convince them that it’s a really cost effective way of preventing species extinction.

We work with local partners to acquire unproductive land, get rid of the cattle, and replant those areas in native trees, establishing habitat connections. In doing that, we also are able to provide a source of income for local communities.

How does SavingSpecies generate impact?

What we do is reconnect forests by building what we call habitat corridors.

We have a mapping site, which maps out the key places in the world where species are at risk, and then we know from lots of detailed scientific studies the consequences of fragmented habitats. We’ve done a huge amount of research that shows that small, isolated fragments of habitat lose species and so we’re in the business of re-connecting landscapes to make them viable for species.

We also want to empower local conservation groups by helping them raise money to restore habitats. I wanted to build an organization that would help them, that would reward them, that would give them the resources and the scientific capability that they need. Moreover, you can see our results from space. You can go to Google Earth, and you can see the landscapes that we have reconnected with our tree planting.

Where are SavingSpecies’ projects?

We currently have ten projects in six countries. We have projects in the Andes. There’s Colombia and Ecuador, in the Coastal Forest of Brazil, and in places like Sumatra…

The site we work in Sumatra is the only place that has elephants, rhinos, tigers and orangutans in the same place. It’s a big patch of forest, but there’s a deep gash into that forest where agriculture has spread along the valley. But elephants and other species want to cross from one patch of forest to another which causes a lot of damage to local people. So we’re creating a forest corridor so that the elephants and other species can move between those patches safely and not bother people; they have freedom to roam.

What do you believe is the best practice for conservation?

Conservation is always local.

The people who live in these areas have lived there for generations. Their lives are there. What we can do is to work with them in a respectful way and see if we can help them make different choices for their lives.

Having local partners solves a lot of problems because they understand the local issues. There’s no way I could go into those places and tell those people what to do. What I can do is help local groups. I can empower local groups so they can solve the problems.

Solving problems is not always easy, but they are idiosyncratic. A problem one part of the world has will be dffierent to a problem in another. It’s always local, and you’ve got to work with people who understand the local politics.

When I look at local, small local conservation groups around the world, I’m hugely impressed by them. These are not famous organizations. These are small, local groups of people. They’re often very passionate about the places where they live and the places that they care about.

What is the scientific process that you follow?

We’re working on scientific papers now to try and identify exactly where the places in the world are that have not been protected properly, places that are the priorities for establishing national parks and other protected areas. Now that work will take me a year or a couple of years to finish with my team. We’ll then publish a paper. That will probably take another year, and it might be several years beyond that before we can make practical actions from that.

When you finally get to that act of planting a tree, it’s enormously rewarding.

It’s that continuum from really rather esoteric, sometimes rather theoretical science, through to the empirical science, through to the practical applications of that science, right down to planting a tree. Some of the things that I’m doing now are consequences of science that I did a decade ago.

We are very energetic at using our science to make a difference.

Do you ever plant the trees yourself?

Oh, you bet. I think that’s the part I like the most.