The Lungs of the Planet Are Burning

September 3, 2019: Rewilding Earth

As the world watches the Amazon fires rage, destroying one of our most important global treasures there is only one question on everyone’s mind:

Can we survive this unchecked destruction?

In his recent article for Rewilding Earth, Stuart Pimm, President of Saving Nature, shares his insights into the Amazon fires and explains the potential consequences.

Days of Fire

by Stuart Pimm

Fly from the USA to Rio de Janeiro and choose a day-time flight. Reject all demands to lower your window shades. You must not miss the view. One heads southeast, crosses Cuba, and makes landfall near Caracas, Venezuela. The next two and a half hours are a planetary spectacular, while the final three are apocalyptic.

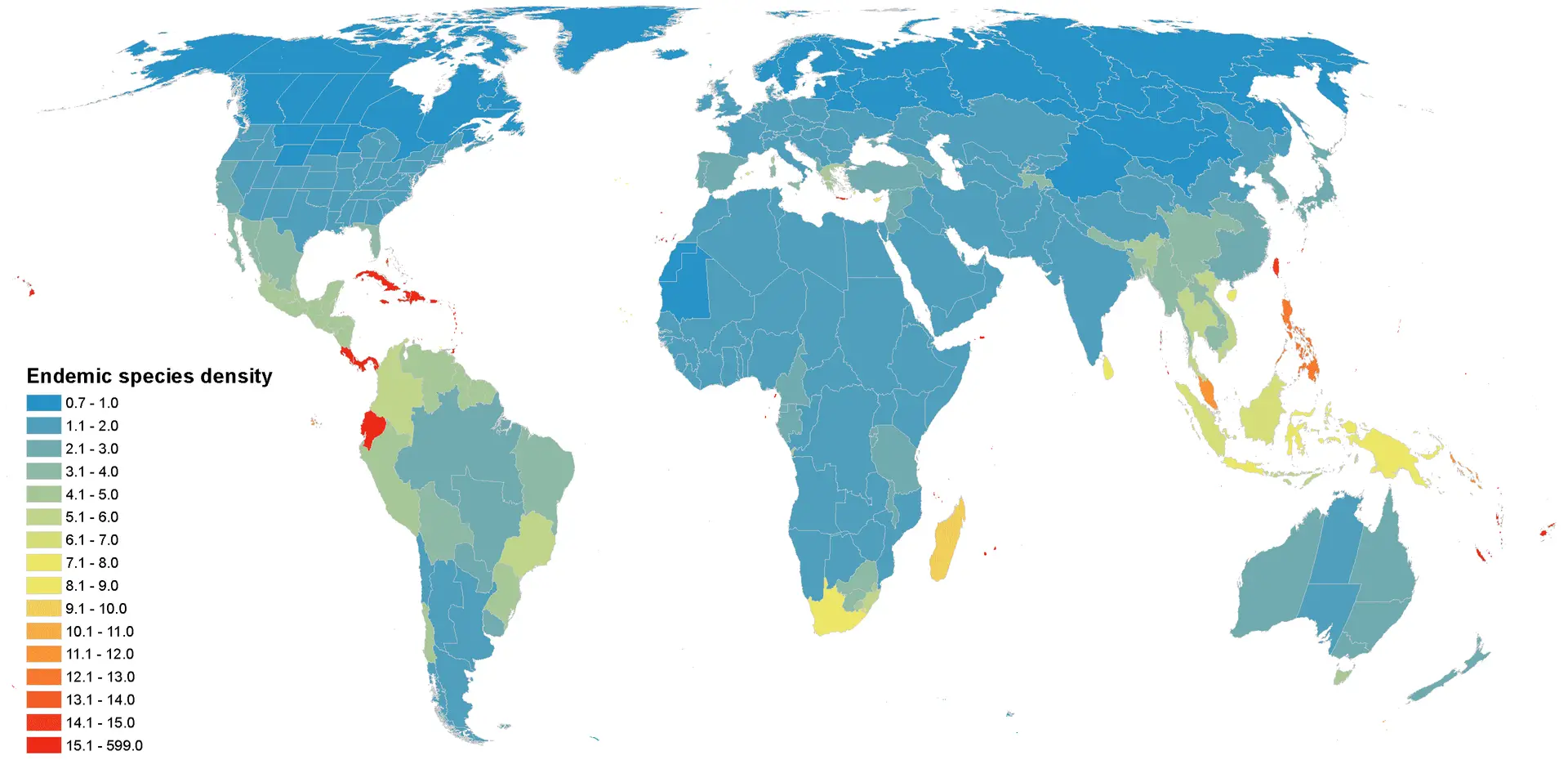

The transect from Caracas to Manaus on the Amazon shows vast, unbroken tracts of forest. I’ve done this on crisp, clear days and, on magical ones, when the tepuis rise above low-lying mist. They inspired Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World. I don’t think undiscovered dinosaurs live there, but undiscovered species? Bet on it.

At Manaus, the black waters of the Rio Negro, coming in from the north, meet the coffee-coloured ones from the Andes. From the plane, I see they refuse to mix for a long way downstream. Unbroken forest returns – but not for long. Soon, there will be huge columns of smoke rising to the height of the plane, their plumes trailing downwind for as far as we can see. All too soon, thick grey smoke will completely cover the ground below. It will continue for most of the rest of the journey.

No other journey tells me what wonderful places we still have of our planet — and how we might lose them in a generation.

Click here to read the entire article.