Biodiversity Needs You – and your Smartphone!

May 9, 2011

by Stuart Pimm

Biodiversity Needs You and Your Smartphone

Our knowledge of biodiversity is not good. We don’t know the names of most species. For the ones that we do, we don’t know where they once lived, let alone where they live now. It’s even worse for species that are rare, for they may soon not live anywhere.

Now, armed with your iPhone and a great new app, you — and I do mean you — can change all that.

First, the prosaic details. We have over a million scientific names for animals and about 350,000 names for flowering plants. There are probably another 15% more flowering plant species waiting to be discovered.

For animals — which are mostly insects — best guesses — and I do mean guesses! — involve several million. So, the great majority are unknown.

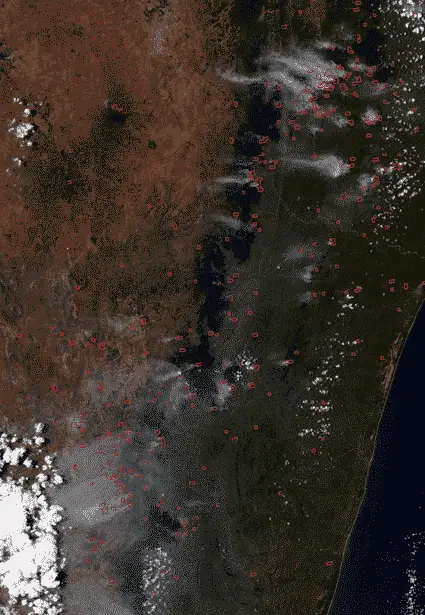

It gets worse. We have maps of geographic ranges for only a tiny fraction of species worldwide — birds, mammals, and amphibians.

For only some countries do we have some other species. The British, living on their cold, damp sceptred isle off the continent at the very bottom of the international league table of biodiversity, seem to have maps of just about everything. “Another Eden”, according to Shakespeare; perhaps, but they don’t have many species to worry about.

How do we produce those maps? The conventional way is to go to museums, look at the specimens there, and record where they were collected.

That’s so 19th Century!

Now, the news. All this is about to change with that 21st Century innovation — the smart phone — and a great new project that started when Dr. Scott Loarie of the Carnegie Institute for Science at Stanford, in California teamed up with Ken-ichi Ueda, a software developer in Silicon Valley.

Scott also lives in Silicon Valley, spends hours in front of a computer writing code, and fills out many of the boxes on the checklist of being a nerdy techie. So you have to watch my video of him: he isn’t.

In the field, he moves from flowers to birds to lizards with an enthusiasm that is instantly infectious. I’ve never met anyone who is so passionate about the outdoors of California and few with such a wide ranging knowledge of its natural history.

“I study the impact of land use change and climate change on biodiversity.”

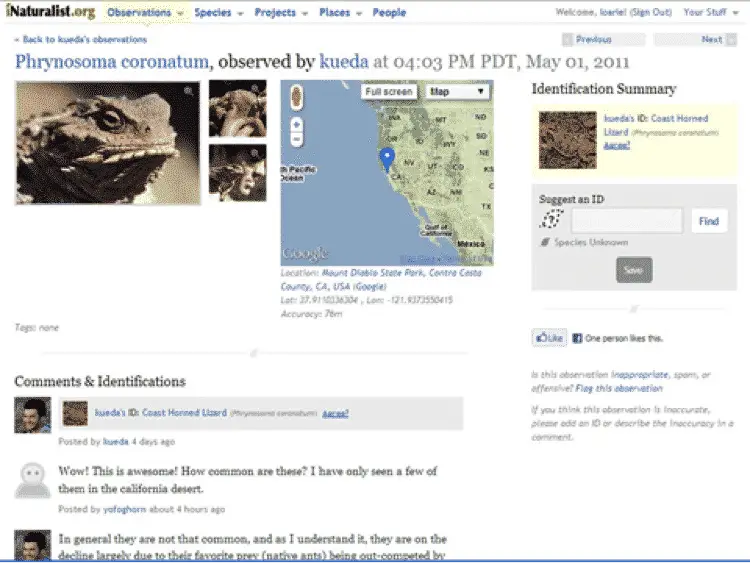

Holding up a coastal horned lizard, (Phrynosoma coronatum) Scott asks:

If I wanted to know where this lizard survives and where it doesn’t, I’d go to a museum and look at all the specimens collected over the last 100 years or so. It used to live in most of the chaparral around here, in the Bay Area of San Francisco.”

“But this is one of those species that is rapidly disappearing. And we’re not exactly sure why. It may be climate change. It may be changes to the ants that make up its diet. It might be the urban sprawl that is isolating its habitat.”

“We need to know exactly where this species persists. And, we need more data.”

Scott’s solution is not an army of well-funded professionals with sophisticated equipment. That isn’t going to happen. He wants you — the citizen scientist and a piece of equipment you likely already own — your iPhone. And, of course the App.

A Picture is Worth 1,000 Words

The simplest way to do things is to take a photo of an animal or plant, upload it to the web — at www.inaturalist.org — along with the location where you saw it.

That’s so late 20th Century!

— not that I want to discourage you. Your smart phone, however, is technology straight from Star Trek. You point, you click, it takes a photo, it records your exact location using the build in GPS and the application uploads this to the web site.

My fellow Trekkies, will naturally sing Commander Data’s song “life forms, tiny little life forms … where are you?” while they do this.

Doing this (whether singing or not) helps with the problem as old as time — we all tend to put things off. After that long day in the field, it’s all too easy to forget. Now, you can record a species the moment you see it.

So what happens if I don’t know the name of my species, or am unsure? The world can help — putting the observation up means others can comment, help, discuss, argue, threatened duels with feather dusters at 50 paces over rival interpretations — all that kind of thing.

Bird people have many places to share their observations. It’s a great community tool, one that works well. Yes, birders make mistakes, or see something that they cannot identify, and make outrageous claims. We know so very much more about where bird species are found worldwide than we do for any other group of species, because citizen science is both nurturing and demanding.

In time, the collections of observations on iNaturalist are going to provide a unique record of where a given species lives. And with more time, we’ll understand more about how that “where” is changing.

iNaturalist also works “backwards,” too.

One can ask: what species am I likely to find on (say) Mount Diablo, in California — where I interviewed Scott?

When Scott first met Ken-ichi, iNaturalist was a social network for naturalists. Scott quickly persuaded Ken-ichi that beyond the potential of getting citizen scientists together with each other for fun was the chance to unite them with scientists to tackle one of the most pressing environmental issues of our age.

iNaturalist is intentionally subversive, in another way too. Scott told me.

What I think is so compelling about iNaturalist is that we are using these technologies — iPhones, apps — that are cutting us off from the natural world. Too often, these are keeping us indoors, narrowing our focus. Now we’re using them to get back out in nature. To the extent we can use this new tool to get people enjoying the outdoors, tuning in with the world around them, that’s a great thing!”