Let’s Talk Carbon!

July 5, 2019

Stuart Pimm

HOW TO BECOME CARBON NEUTRAL

Let’s talk carbon. Saving Nature offsets carbon emissions surprisingly cheaply and, in doing so, helps species adapt to climate change.

This can be a complicated subject. Let’s simplify it.

We ask each supporter for $100 per year. That will make the average US citizen “carbon neutral” — the native trees we plant to restore forests with that money will soak up as much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere that he or she puts into it each year.

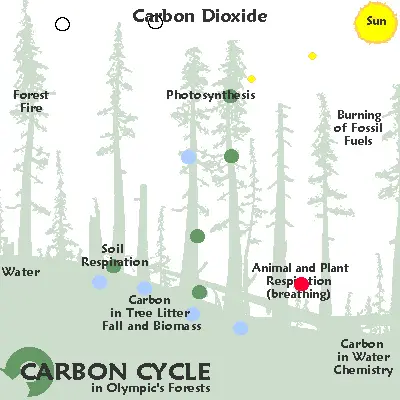

Carbon Dioxide Causes Global Warming

Our various human activities put about 37 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year. That’s from burning coal and gasoline, of course, but also by burning forests.

We measure increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere with great precision and have done so for decades. As the concentration increases, it traps more of the sun’s energy and so the planet warms. That massively disrupts the climate, harming people and biodiversity alike.

How to Become Carbon Neutral

Taking action to erase your carbon footprint is as simple as answering three questions.

1. How much carbon dioxide am I putting into the atmosphere each year?

If you are average and live in the USA, the answer is 16 tons.

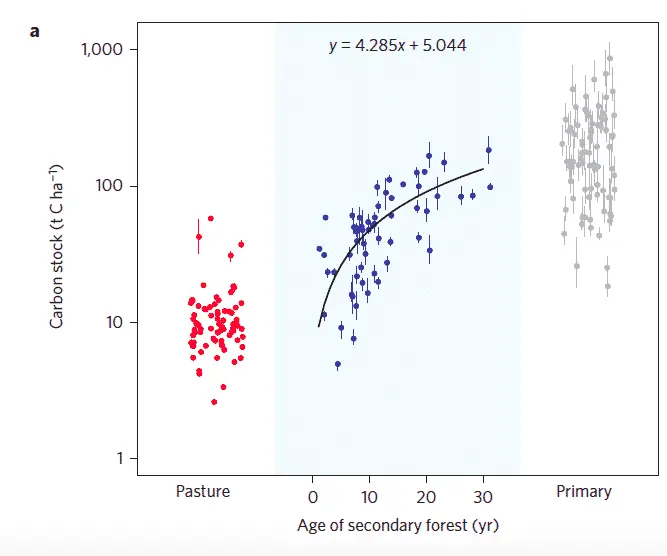

2. How much carbon does a forest soak up?

Growing trees take carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. So how many trees do you need to plant so that you are “carbon neutral?” That is, how many trees with your name on them are needed to soak up — technically, the word is sequester — as much carbon dioxide as your lifestyle produces.

The answer is that the corridors we reforest at Saving Nature soak up about that same amount per hectare per year. Those corridors continue to do that for twenty years or more and at a slower rate thereafter. The bottom line is: help us plant and protect a hectare of forest and you’ll be carbon neutral for decades.

3. And finally, how much does it cost to be carbon neutral?

Tropical forests soak up about 26 tons of carbon dioxide per hectare per year as they grow back. They do so for 20 years — and usually considerably longer. Close enough, buying and reforesting a hectare of tropical forest will offset almost all a typical American’s carbon dioxide emissions for 20 years.

So how much does a hectare cost? Well, that depends on where we help our partners buy land and whether they plant the trees. Apart from some very difficult restorations, for which we solicit support from foundations, our costs are about $4 a ton per carbon dioxide. So about $100 per year will offset a typical American’s carbon emissions. (Other nations have different and usually lower ones.)

4. How to help combat global warming and save species?

We will continue to use both science and savvy to connect, protect, and restore forest corridors. We invite you to join us in this ambitious effort! Donating to Saving Nature puts trees in the ground for biodiversity, and sequesters carbon from the atmosphere.

Please support Saving Nature in fighting global warming — at the same time you’ll be fighting mass species extinctions!