The Golden Lion Tamarin Returns From Extinction

Weighing less than 1.5 pounds, and sporting a mane reminiscent of Africa’s great cats, the tamarin’s survival is particularly perilous. With only 2% of their original habitat remaining, they live in isolated groups in a patchwork of small forests, unable to move and they are facing new challenges.

Succumbing to deforestation and collection for the pet trade, this charismatic species had dwindled to 200 individuals in the wild by the late 1960’s – basically one catastrophe short of extinction.

One Forest is Their Entire World

The Atlantic Forest of Brazil is the only place on earth you will find the golden lion tamarin. These endemic primates thrive in these wet forests. In fact, without adequate habitat, they simply won’t have a sustainable future in the wild.

Once more than a million square kilometers of dense tropical forest stretching from southeastern Paraguay and northern Argentina along the Brazilian coast to just south of the equator, the Atlantic Forest is barely recognizable today.

Centuries of exploitation and population growth have whittled away 95% of this majestic and ancient forest.

Their Heroic struggle

With the wild population disappearing, the tamarins got an unexpected reprieve in the early 1980’s. This second chance was thanks to an ambitious captive breeding and reintroduction program. Working together, zoos around the world carefully managed the captive population genetics. At the same time, ecologists studied habitat, and educators worked with local communities.

By 2007, the reintroduction stalled. Simply put, there wasn’t enough forest for any more tamarins. That’s when the team at Saving Nature stepped in to help changed that. Coupled with the efforts to breed tamarins, we brought expertise in connecting, protecting, and restoring critical forest fragments. Importantly, by making these connections, isolated tamarins would have access to larger forest expanses capable of supporting viable populations.

Our goal was ambitious – to reverse the damage of increasing forest fragmentation and save this irreplaceable primate. To do so, we partnered with Associação Mico-Leão Dourado (AMLD) to create connected lowland habitat that would sustain a viable population. By 2016, the collective effort got results, with their population growing steadily.

Today, the work continues as the challenges to resiliency confronting small populations compound. Sadly, ongoing habitat loss, expanding development, genetic drift, and anthropogenic diseases have reversed some of the gains. But don’t count this tenacious primate out just yet. As support grows, so do their prospects for a sustainable, a third were descendants of those raised in human care.

Saving Golden Lion Tamarins

What We Are Doing To Help

SAVING THE GOLDEN LION TAMARIN

CREATING A NEW LEGACY

OUR FLAGSHIP CORRIDOR

THE FIRST HIGHWAY BRIDGE

PROTECTING RIO'S WATERSHED

THE SCIENCE

MEASURING

RESULTS

PROJECT

VIDEOS

SAVING THE GOLDEN LION TAMARIN

Golden lion tamarins are once again born in the wild a er coming back from the verge of extinction. (Photo by Luis Paulo Ferraz)

THE ATLANTIC FOREST OF BRAZIL IS THEIR ENTIRE WORLD

Among the most threatened species in what remains of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest is the golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia). Weighing less than 1.5 pounds, and sporting a mane reminiscent of Africa’s great cats, their survival is particularly perilous. As a result of widespread deforestation, only 2% of their original habitat remains. Today, they live in isolated groups in a patchwork of small forests, unable to move and they are facing new challenges.

THEIR HEROIC STRUGGLE

Succumbing to deforestation and collection for the pet trade, this charismatic species had dwindled to 200 individuals in the wild by the late 1960’s – basically one catastrophe short of extinction.

With the wild population disappearing, they got an unexpected reprieve in the early 1980’s, thanks to an ambitious captive breeding and reintroduction program. Seeing the importance of returning golden lion tamarins to the wild, zoos stepped in to help. Joining forces, a network of zoos carefully managed the captive population genetics, ecologists studied habitat, and educators worked with local communities.

By 2007, the reintroduction stalled. Simply put, there wasn’t enough forest for any more tamarins. That’s when the team at Saving Nature helped changed that, joining the effort to save the golden lion tamarin by helping to connect, protect, and restore critical forest fragments. By making these connections, isolated golden lion tamarins would have access to larger forest expanses capable of supporting viable populations.

Our goal was ambitious – to reverse the damage of increasing forest fragmentation and save this irreplaceable primate. To do so, we partnered with Associação Mico-Leão Dourado (AMLD) to create connected lowland habitat that would sustain a viable population of golden lion tamarins. By 2016, the collective effort got results, with the population of tamarins growing steadily, a third of which being descendants of golden lion tamarins raised in human care.

.

Brazil embraced the golden lion tamarin as a national symbol on the 20 Reais bill.

Golden lion tamarins went from a little-known and under-studied primate to a national symbol in Brazil, featured on a postage stamp and on the R$20 bil

THE WORK CONTINUES

Today, the work continues as the challenges to resiliency confronting small populations compound. The combination of ongoing habitat loss, expanding development, genetic drift, and anthropogenic diseases have reversed some of the gains. But don’t count this tenacious primate out just yet. As support grows, so do their prospects for a sustainable future.

CREATING A NEW LEGACY

PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY AND WATER SECURITY IN BRAZIL’S ATLANTIC FOREST

For over a decade, the team at Saving Nature has worked to restore and protect the Atlantic Forest of Brazil.

To do so, we joined forces with two local NGOs, Associação Mico-Leão Dourado (AMLD) and Reserva Ecológica de Guapiaçu (REGUA) to begin the work of restoration and protection. Together, we are piecing together a beachhead for biodiversity and a sustainable long-term future for a critical watershed, which serves 13 million people living in Rio de Janeiro.

Since our first project with AMLD launched in 2007, we have successfully reconnected two isolated forest fragments across a road to create a continuous protected area for the golden lion tamarin. We are now working to create our second wildlife corridor, which integrates a protected reserve with the first forested highway bridge in Brazil to create an even more expansive area for tamarins and other species.

Building our success, we inaugurated our latest project in 2019, supporting our local partner REGUA in their efforts to restore the health and resiliency of an important watershed for Rio de Janeiro. This multi-year project has the potential to ensure a sustainable future for biodiversity, communities, and the planet.

HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

We hope our long-term commitment and collaborative approach among NGO’s, zoos, local communities, individuals, and governments working in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil to save this vanishing ecosystem and its biodiversity will serve as a model for how to achieve effective and efficient ecosystem protection and restoration through cooperation and strategic action.

OUR FLAGSHIP CORRIDOR

THE FAZENDA DOURADA CORRIDOR

Our flagship project in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest launched in 2007. Aptly named Fazenda Dourada, meaning golden farm, it was an important connection for golden lion tamarins and other species.

Twelve years in the making, it has become a functioning wildlife corridor, linking the isolated federal União Biological Reserve to forests to the west and at higher elevations. Today, the corridor and those forests to the west are now included in the much expanded reserve. Over time, the trees have matured into a continuous canopy connecting two forests over a road, creating a migratory pathway for the endangered golden lion tamarin and potentially thousands of other imperiled species to travel through previously degraded and fragmented landscapes.

EVIDENCE OF THE FOREST RETURNING CAN BE SEEN FROM SPACE

As shown in these Before and After photos, what was once a degraded, impassable landscape for the tamarins and other species is now a passage to more resources. As a result of the efforts by Saving Nature and our long-term local conservation partners, there is now considerably more accessible habitat.

In 2019, we confirmed the corridor was working, with tamarins crossing into an area from which they had previously been absent. Foxes, crab-eating raccoons, otters, and birds also now live in the corridor.

This corridor has become a model for future restoration projects in Brazil and other biodiversity hotspots around the world.” says Stuart Pimm, President of Saving Nature. “While the iconic golden lion tamarin served as the flagship species for this restoration because it’s such a charismatic animal, the model will also serve many other unique species.”

THE FIRST HIGHWAY BRIDGE

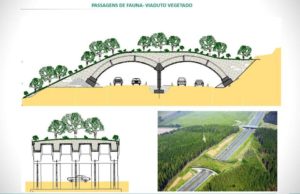

Detail of restoration area with a habitat bridge that creates the forest corridor for golden lion tamarins crossing highway BR-101 (Image courtesy AMLD)

ONE HIGHWAY FOR PEOPLE, ANOTHER FOR WILDLIFE

The need for a better and safer highway connection between northern and southern Brazil created another potential challenge for golden lion tamarins and other species. Widening the BR-101 highway from two lanes to four risked creating a manmade barrier, virtually impossible for them to cross.

Fortunately, the Brazilian government had the foresight to require that the highway construction plant include a tree topped bridge across the new highway. Notably, the first of its kind in Brazil, the forested highway bridge creates a passageway for tamarins and other species trying to cross.

COMPLETING THE CONNECTION

The only missing piece in the plan was the connection between the bridge and the Poço das Antas reserve. That’s where Saving Nature and our multi-year partnership with DOB Ecology and Associação Mico Leão Dourado (AMLD) come in! Together, we seized upon an extraordinary opportunity to capitalize on this innovative highway crossing. We began by identifying a strategic parcel of land located at the outlet of the bridge. Next, we raise the funds to acquire the property and set it aside for restoration.

The property we helped purchase on behalf of AMLD connects two large surviving fragments of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and establishes an important gateway into the Golden Lion Tamarin Reserve. In addition, it creates a much needed safe zone for a host of species crossing the highway. This is an especially important step toward our vision to of having enough forest to support a viable tamarin population far into the future. Because of relentless threats from road development, healing the Atlantic Forest is the only hope for survival of golden lion tamarins and the wealth of biodiversity in the Atlantic Forest.

RESTORATION WORK BEGINS…

While the bridge construction is underway, the team at AMLD has begun restoring the corridor. They have installed fencing to keep out grazing cattle and planted a mix of native trees. Over time, the young trees will mature, shading out the grasses and providing cover for species moving through the corridor.

Click here to see a panoramic image of the recovering corridor.

PROTECTING RIO'S WATERSHED

The Guapiaçu watershed in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil is more than just a collection of trees. In fact, it provides many important services. For example. it shelters biodiversity and quietly provides ecosystem services for the region, including fresh drinking water for 13 million residents of Rio de Janeiro. Over time the watershed has lost some of its resiliency as agriculture transformed forests to farms and urbanization encroached deeper into the region.

REBUILDING A HEALTHY FOREST

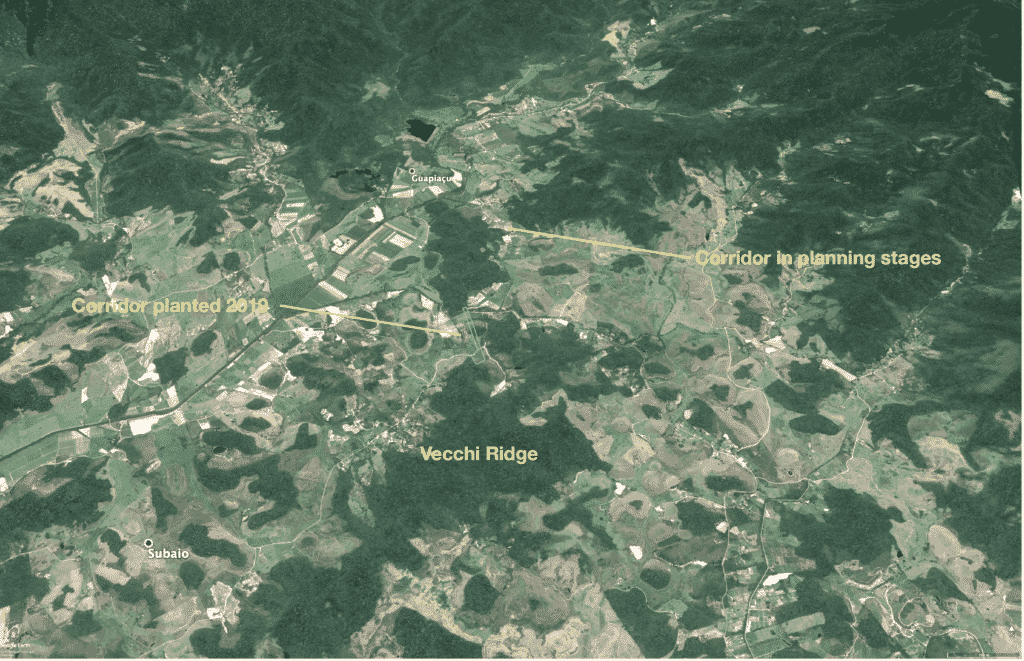

In 2019, Saving Nature began working with REGUA to restore connections among small isolated forests to regain some of what has been lost. In this now mixed landscape of farmland, fragmented forests, and new housing developments, it is the only real hope for gene pools of stranded biodiversity to move around.

To secure a foothold in connecting several small isolated forests, we are creating a micro-corridor in the lowlands. Although small, this 6 hectare connection is critical to linking the 2,500 hectare Vecchi Ridgeline with the 200 hectare Onofre Cunha.

Having acquired the land, REGUA is busy with restoration efforts, creating a forested corridor with native trees to allow birds and animals to move through and beyond to a 100,000 hectare forest block. Concurrent with the restoration work, Saving Nature began our baseline monitoring program of annual drone surveys and ongoing camera trap surveillance.

We are also scoping additional opportunities to expand the protections for this refuge for biodiversity and important source of clean drinking water for Rio’s growing population.

THE SCIENCE

MAPPING IS CENTRAL TO WHAT WE DO AT SAVING NATURE

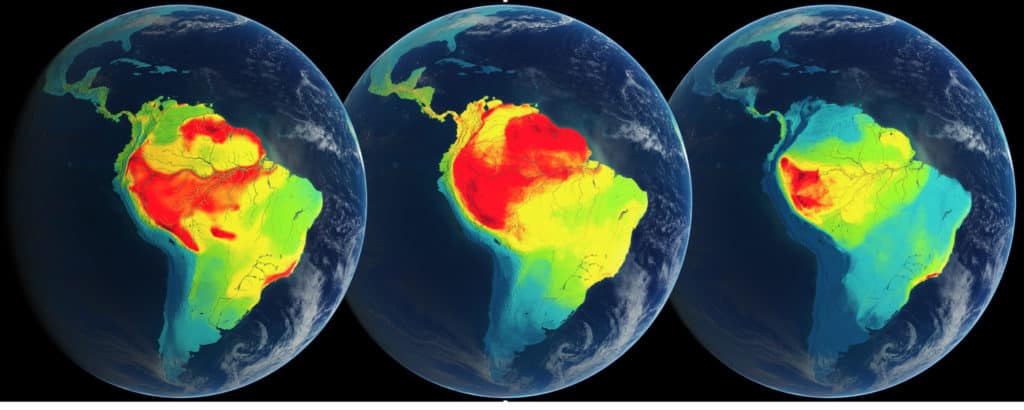

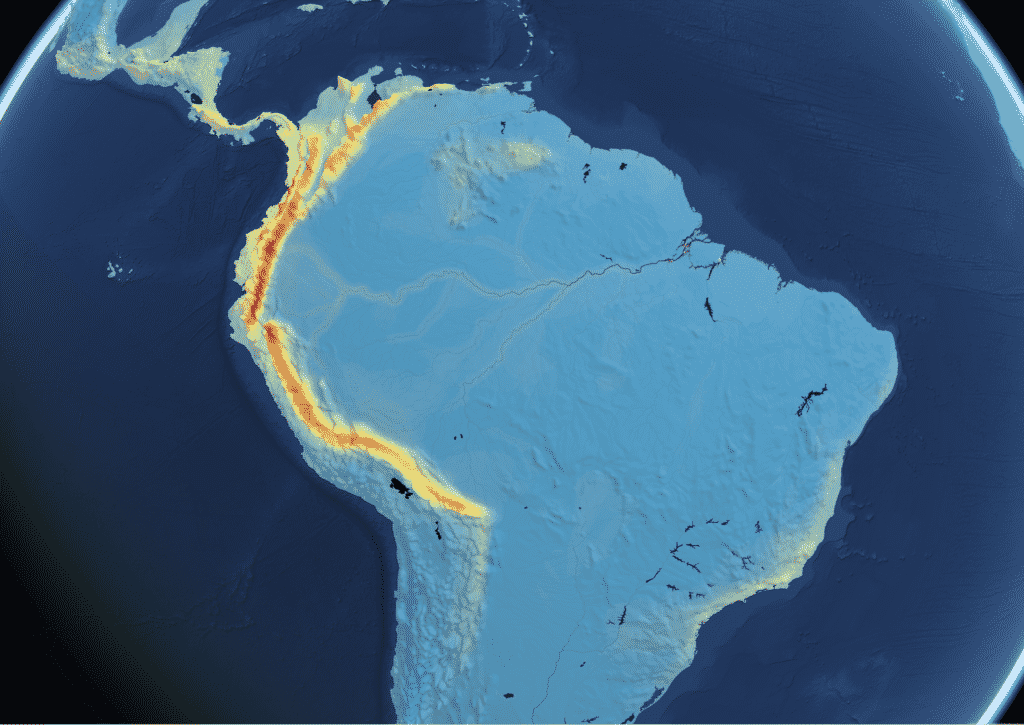

The process we use at Saving Nature is to start with strategic maps that set the areas that are our priorities. We then zoom in on the key places within them to map exactly where we should put our conservation actions into practice. The International Cosmos Prize, awarded to Professor Pimm in 2019, explicitly recognized him for developing this approach.

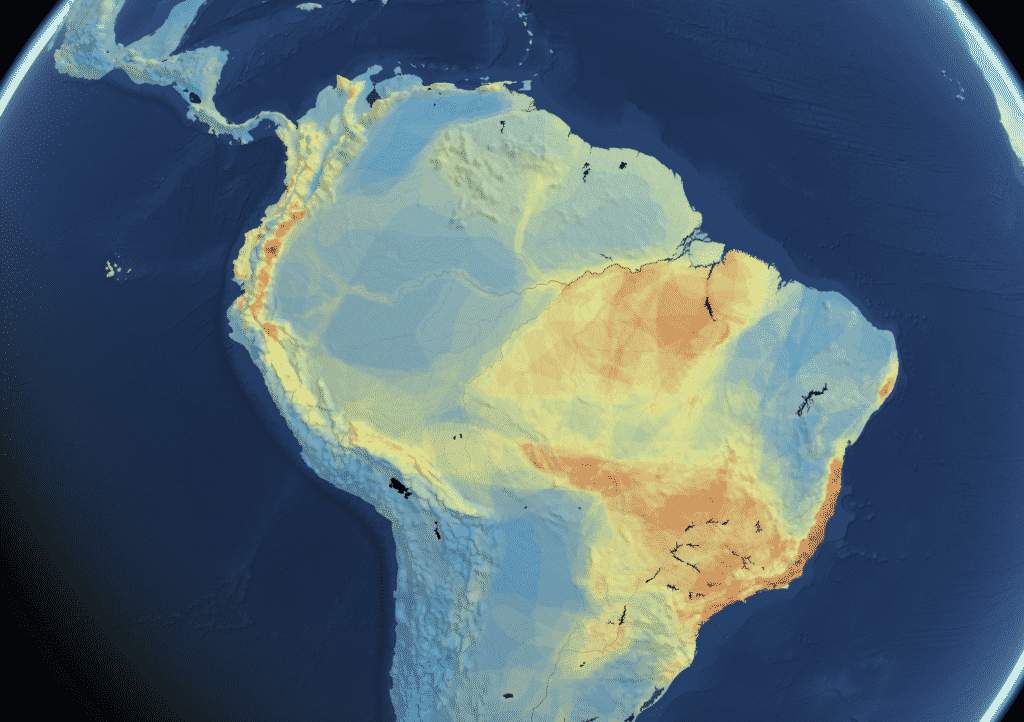

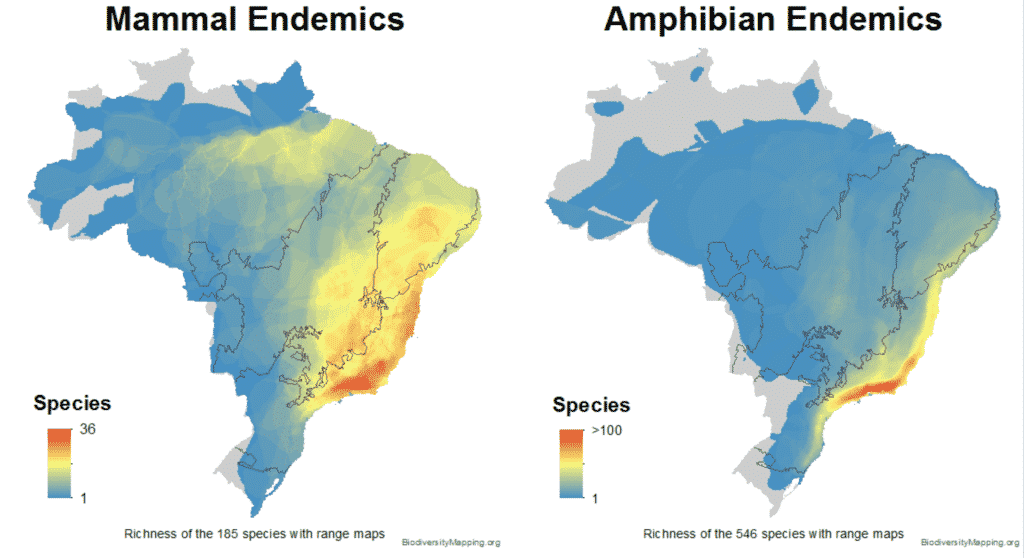

These maps illustrate what we do for South America. The first map is of the species of birds, mammals, and amphibians. Red means more species, blue means fewer. The areas of tropical moist forest — including the Amazon and the coastal forests of Brazil —contain the most species.

The second map is where small-ranged species of birds live. By “small-ranged” we mean the half of all bird species that have smallest ranges. This map may surprise: why aren’t there more species in the Amazon? The answer is that while there are more species, must most have relatively large geographical ranges.

The importance of this map is that species with small geographical ranges are much more likely to be threatened with extinction. Indeed, the next map is of threatened bird species. It’s broadly similar to the previous one. The largest difference is that there are relatively more threatened species in coastal Brazil, because so much of the forest has been lost.

It’s not just birds — the species of mammals and amphibians with small ranges concentrate in Brazil’s coastal forests too. Species with small ranges are often endemic to the country, i.e. found no where else.

These maps — and many like them for different continents and the oceans are from our companion website www.biodiversitymapping.org

We don’t have maps this good for plants, but they also point to coastal Brazil as a priority and, moreover, to the State of Rio de Janeiro as its center.

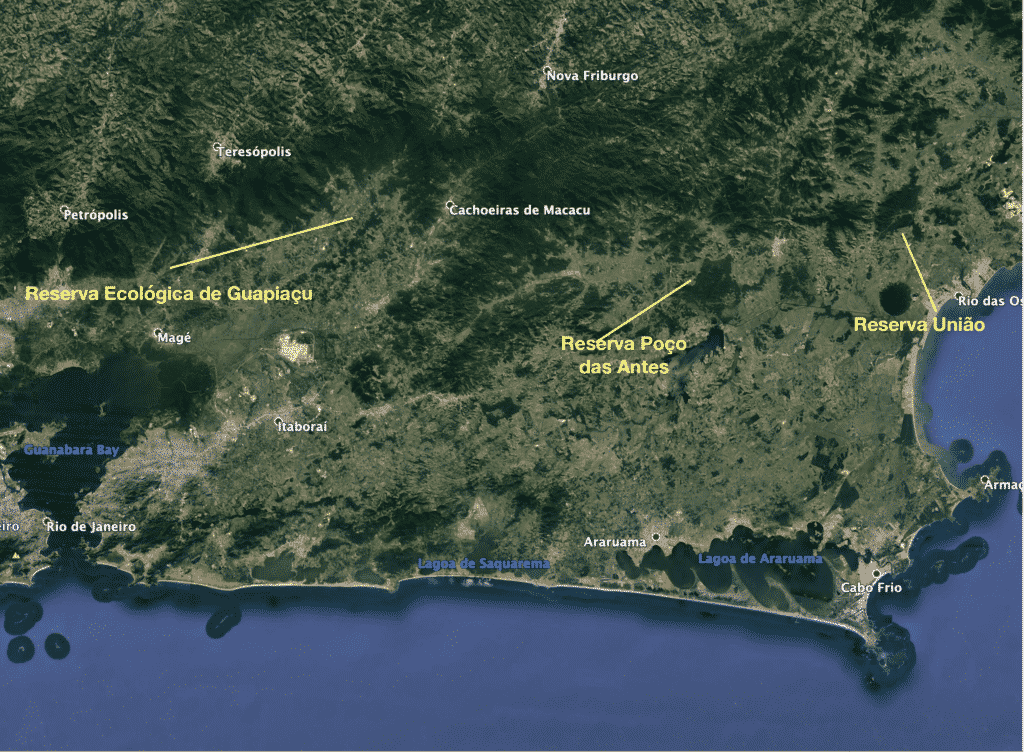

Let’s take a closer look. This satellite image shows the area from the eastern side of the city of Rio de Janeiro, eastwards for about 200 kilometers.

There’s an east to west mountain range that’s still mostly forested and lowlands to the south of it. Little forest remains in the lowlands — its been cleared for crops and cattle pasture. What’s left is forest fragments of different sizes.

A lot of of science tells us that forest fragments lose species over time — with smaller ones losing more species and losing them faster than do large ones. This tells us de-fragmenting isolated forests should be a most effective conservation tactic.

Saving Nature does this at three sites:

Corridor 1: Reserva União

Corridor 2: Reserva Poço das Antes

Corridor 3: Reserva Ecológica de Guapiaçu

Sources

1. Patterns of Vertebrate Diversity and Protection in Brazil, Clinton Jenkins, Maria Alice S. Alves, Alexandre Uezu, Mariana M. Vale

MEASURING

RESULTS

The achievements in preventing the loss of biodiversity, restoring ecosystem health, and improving the quality of life for the local and global communities ultimately define our success. Since our projects have a long-term time horizon, we use progressive measures of success:

1. PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY

Movement of wildlife is a critical milestone for validating our work, demonstrating the species are repopulating diminished forests, increasing genetic diversity, and improving resilience. We begin with baseline metrics of mammal and bird species in the protected areas that should disperse through the corridor over time. Then, we evaluate project effectiveness based on the diversity of species moving through the corridor over time. In addition, we install camera traps throughout the corridor, both on the ground and in the canopy to record the species moving through.

2. RESTORING ECOSYSTEM HEALTH

Once we launch a new corridor project, we establish the baseline forest cover. We then annually monitor the quality of the landscape, which improves as forests return, gradually restoring “ecosystem services”, such as preventing silting and landslides. Our team conducts annual site visits to assess reforestation progress using ground surveys, drones, and satellite imagery. Over the longer term, we measure success in completing the corridor connection, based on the percentage of land we have acquired to prevent further destruction.

3. MITIGATING CLIMATE CHANGE

Once reforestation is underway, we begin to accrue carbon sequestration benefits to offset carbon dioxide emissions. As the trees mature, they soak up at least 5 tons of carbon per hectare per year. On average, each US consumer produces about 7 tons of carbon per year.

OUR RESULTS IN THE ATLANTIC FOREST OF BRAZIL

Our corridor reforestation project with AMLD to secure a future for the golden lion tamarin and other species has achieved several milestones since its launch in 2007. To date, Saving Nature completed the acquisition of 346 hectares of degraded cattle pasture to establish two corridors for the golden lion tamarins. In addition, we secure hectares of land for the Rio watershed project to create our micro-corridor connection between two important ridgelines.

Restoration work in ongoing in all three corridors, which are not at various stages of regeneration. Specifically, the Fazenda Dorouda corridor is largely restored and continues to mature. In addition, replanting is underway in both the second tamarin corridor and the REGUA corridor. Looking to the future, we have planned out our next phases of land acquisitions for REGUA, which will be implemented as funding for the project allows.

In 2018, we also began the work of restoration and monitoring. We now have a network of 25 camera traps installed at key points throughout the corridor to track wildlife movement. The purpose of our camera traps is to record the species moving through the corridor to verify species are dispersing as anticipated. Our camera traps are monitoring the area on a 24/7 basis, recording both photos and videos.To date, we have recorded over 620 images and 41 videos, documenting 15 species moving through the corridor, including puma, ocelots, anteaters, coatis, birds, and reptiles.

Having significantly expanded our corridor surveillance program, we have partnered with Duke University. Our goal is to mentor the next generation of conservation scientists through practical experience. With their help, we are measuring results, building a database on the movement of species through the corridor, and modelling how species adopt the corridor to advance conservation science.

Regeneration of habitat is an important measure of project success. To do so, we also continue to monitor habitat restoration progress with an annual drone survey to evaluate progress in establishing a continuous canopy. Moving forward, this data will be the foundation for modelling forest regeneration in tropical landscapes to determine the pace of forest recovery.

PROJECT

VIDEOS

« Prev1 / 1Next »

VIADUTO VEGETADO MICO-LEÃO-DOURADO / GOLDEN LION TAMARIN WILDLIFE BRIDGE

VIADUTO VEGETADO MICO-LEÃO-DOURADO / GOLDEN LION TAMARIN WILDLIFE BRIDGE South American cougar (puma concolor)

South American cougar (puma concolor) Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris)

Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) Lessor Grison (Galictis cuja)

Lessor Grison (Galictis cuja) Black-and-White Tegu (Salvator merianae – Teiu)

Black-and-White Tegu (Salvator merianae – Teiu) Southern Tamandua / Lesser Anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla) hitches a ride

Southern Tamandua / Lesser Anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla) hitches a ride Meet The Atlantic Forest of Brazil

Meet The Atlantic Forest of Brazil Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) Rumble in the Jungle Heavyweight Championship Bout

Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) Rumble in the Jungle Heavyweight Championship Bout Southern Tamandua / Lesser Anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla) looking for ants

Southern Tamandua / Lesser Anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla) looking for ants Happy World Tapir Day (April 27th)

Happy World Tapir Day (April 27th) Black-and-White Tegu Salvator merianae (Teiu)

Black-and-White Tegu Salvator merianae (Teiu) Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris)

Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) Colors of Atlantic Forest« Prev1 / 1Next »

Colors of Atlantic Forest« Prev1 / 1Next »

This ambitious project would not have possible by the generous support of DOB Ecology, a charitable foundation based in the Netherlands. Their support for conservation projects in Latin American and Sub-Saharan Africa makes an incredible difference for biodiversity. Their concern for the Atlantic Forest of Brazil made it possible to capitalize on this unique opportunity. Together, we are amplifying AMLD’s progress from two decades of work to secure a future for these tenacious primates.

help SAVE THE GOLDEN LION TAMARIN

Copyright 2025 Saving Nature | fGreen Theme powered by WordPress

Subscribe to our channel

Subscribe to our channel