Why Boycott Madagascar’s Rosewood and Ebony?

October 6, 2009

Representatives of Malagasy civil society, conservation and development organizations and the international community issued a statement today lamenting the ongoing destruction of Madagascar’s last fragments of forest for the illegal harvest and export of precious woods. Consumers of rosewood and ebony products are asked to check their origin, and boycott those made of Malagasy wood. The full statement is at the bottom of this page.

Conservation biologist Stuart Pimm writes about his observations of the diversity in Madagascar and how the current pillaging of the country’s natural heritage threatens not only to destroy decades of conservation work, but also ruin the one chance that communities adjacent to national parks have to escape poverty.

The Call to Boycott Madagascar’s Rosewood and Ebony Explained

By Stuart L. Pimm

Special Contributor to NatGeo News Watch

Madagascar has long been the worst country to be a tree. In the last year, things have got even nastier.

“To how many continents have you traveled with National Geographic,” people ask me. “Eight,” I reply with complete confidence. “But there are only seven continents!” I will not win the National Geographic Bee. I am unmoved, nonetheless.

Madagascar is the eighth “continent,” and no one who loves the great diversity of life on Earth would disagree. Almost everything a naturalist sees in Madagascar is unique to the place.

There are the lemurs, of course. But even to a birdwatcher, broadly familiar kinds of birds are so special to the island that they must have “Madagascar” in front of their names: Madagascar partridge, Madagascar pochard, Madagascar buttonquail–and on down a long list. It turns out that most of these birds are not all that familiar–they are peculiarly from Madagascar.

Simply, Madagascar is an entirely isolated world. It has landscapes that could be the sets for science fiction movies, and one odd lemur, the aye-aye, that is too incredible to belong in one.

Most of Madagascar’s trees–and other plants–are also unique.

Sadly, Madagascar is a wretchedly bad place to be a tree, even in the best of times. Most of the country has been deforested. A coup earlier this year ejected a democratically elected president. In the lawlessness that has followed since, the remaining trees are getting an even worse deal than they have in the past.

Along with other members of National Geographic’s Committee for Research and Exploration (CRE) a few years ago, we flew from the capital city, Antananarivo, towards the northeast end of the island–the Masoala peninsula, a place of exceptional diversity.

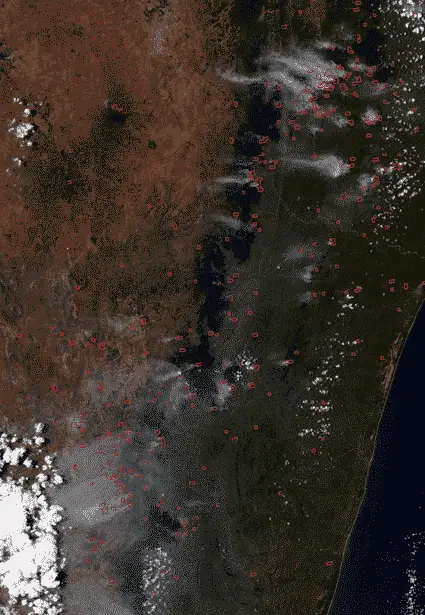

But almost as soon as we took off there was smoke in the air–and on the ground beneath us we could see fires, small and large. I know from looking at satellite images that many are large enough to be seen from space.

I first traveled to Madagascar with my then graduate student, Luke Dollar–now a National Geographic emerging explorer. On the ground, the problem was obvious. To clear their fields or to give a short flush of nutrients for the grasses on which their cattle feed, villagers set fire to the land.

The remnant patches of forest–often in national parks–would go up in flames too as the fire spread into them. Wherever we traveled, we saw forest edges that had been recently burned.

“Why should they care,” Luke asked. “They get no benefit from parks.” Rural areas of Madagascar contain some of the poorest people on Earth.

Luke, and my fellow CRE member, Professor Patricia Wright, spend their energies ensuring that poor people near Madagascar’s parks do benefit from the sanctuaries.

Luke founded a small restaurant near one park, for example. The committee ate there during our visit. (Rice and beans, French fries and eggs–a definite improvement on the food we ate during our field work in earlier years.)

With an income stream from the restaurant, the children in the village were all in school. Literacy is the first step on the ladder out of poverty.

Pat’s efforts in Madagascar are even more extensive. Near the Ranomafana National Park her lemur research helped establish, she’s created the research station where almost every young conservation biologist–Malagasy or foreign–goes to learn the craft.

“I watched an aye-aye from the dining room of the research center,” she told me on my first visit to the facility, bursting with obvious pride and excitement.

An entire community has come to depend on the benefits of Ranomafana and the money it generates from visitors.

All this makes what is happening now in Madagascar so tragic.

Reports from the field make it clear that in the last year there has been a surge in logging inside protected forests. The trees involved are mostly “rosewood” and “ebony,” Peter Raven told me.

Peter is the chairman of National Geographic’s Committee for Research and Exploration and has overseen many National Geographic grants to local and international researchers in Madagascar.

In his other capacity as president of Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter is responsible for a large staff in Madagascar. Missouri Botanical Garden runs a multitiered botanical training program in the country, with a network of local collectors working in parks and reserves.

Peter Raven is truly in the middle of the country’s research and conservation.

Rosewood and Ebony

I asked Peter for more information about the rosewood and ebony trees, for these common names are misleading.

“Rosewood is Dalbergia, a legume, and it has some 47 endemic species in Madagascar, and Diospyros, ebony, which is also being logged, we now believe has nearly 200 species–a remarkable array of endemics in each case,” he told me. (“Endemics” are those species found only in the country.)

I’ve not seen the illegal logging firsthand in Madagascar. But I know the way it works in other countries. The essential ingredients are a good river and bad policing. You select a tree near a river, fell it with a chain saw, float it downriver. There will always be someone to pay for the chain saw, so long as he doesn’t get caught.

So who buys these trees? Try typing “Madagascar rosewood” into Google. The first couple of hundred entries are almost all about guitars. And I gave up checking after that.

There’s a lot of money to be made in poaching trees that provide beautiful wood that we desire. Do you know where your guitar came from?

There was a time when people thought that leopards looked best as skins draped over expensive women. Then we learned that they never look more beautiful than when they’re in their natural habitat.

I hope there will be a time when we’ll agree that there is nothing so lovely as a tree. (I borrowed that.) Except, perhaps for the lemur sitting in it.

But more than anything, there is nothing more precious to behold than the children in the schools that tourist dollars build.

Text of statement released today by conservation groups regarding forests and export of wood from Madagascar:

Malagasy government’s decree for precious wood export will unleash further environmental pillaging

Recently Madagascar’s transitional government issued two contradictory decrees: first, the exploitation of all precious woods was made illegal, but then a second allowed the export of hundreds of shipping containers packed with this illegally harvested wood.

Madagascar’s forests have long suffered from the abusive exploitation of precious woods, most particularly rosewoods and ebonies, but the country’s recent political problems have resulted in a dramatic increase in their exploitation.

This activity now represents a serious threat to those who rely on the forest for goods and services and for the country’s rich, unique and highly endangered flora and fauna.

Precious woods are being extracted from forests by roving and sometimes violent gangs of lumbermen and sold to a few powerful businessmen for export.

Madagascar has 47 species of rosewood and over 100 ebony species that occur nowhere else, and their exploitation is pushing some to the brink of extinction.

Those exploiting the trees are also trapping endangered lemurs for food, and the forests themselves are being degraded as trees are felled, processed and dragged to adjacent rivers or roads for transport to the coast. No forest that contains precious woods is safe, and the country’s most prestigious nature reserves and favoured tourist destinations, such as the Marojejy and Masoala World Heritage Sites and the Mananara Biosphere Reserve, have been the focus of intensive exploitation.

Currently thousands of rosewood and ebony logs, none of them legally exploited, are stored in Madagascar’s east coast ports, Vohémar, Antalaha, and Toamasina. The most recent decree will allow their export and surely encourage a further wave of environmental pillaging.

Malagasy civil society, conservation and development organisations and the international community are united in lamenting the issue of the most recent decree, in fearing its consequences and in questioning its legitimacy. Consumers of rosewood and ebony products are asked to check their origin, and boycott those made of Malagasy wood.

October 6, 2009

CAS California Academy of Science

CI Conservation International

DWCT Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust

EAZA European Association of Zoos and Aquaria

ICTE Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Environments

MBG Missouri Botanical Garden

MFG Madagascar Fauna Group

The Field Museum, Chicago

Dr Claire Kremen, University of California, Berkeley

Dean Keith Gilless, University of California, Berkeley

Robert Douglas Stone, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

WASA World Association of Zoos and Aquariums

WCS Wildlife Conservation Society

WWF World Wide Fund for Nature

Zoo Zürich