The Search for the Grey-winged cotinga

May 30, 2011

by Stuart Pimm

Not all National Geographic expeditions go smoothly.

All adventures end at precisely the same point. Thirty seconds into the hot shower, a stream of dirty water runs down the drain. It takes with it the mud and dried blood, changing skin color from blotchy grey to pink, uncovers the until-now forgotten scrapes and cuts, and exterminates the thriving ecosystem of bacteria and fungi, each with its own distinct and pungent smell, to which my skin had been playing host.

This is exactly when one has the first dangerous notion that the last days or weeks might have been fun.

This expedition to remote and unexplored Brazilian mountaintops to lookfor one of the world’s rarest birds was born in my comfortable, air-conditioned laboratory. Professor Maria Alice dos Santos Alves of the State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and I are sitting in front of a large computer monitor. On screen is a satellite image of the State of Rio de Janeiro. Overlaying other information, the computer tells us is that one of the biologically richest areas of the planet has been barely explored.

Someone has to go — not “because it’s there” — but precisely because in short order it may not be. This is one of the most damaged and threatened ecosystems on Earth. Within days, Maria Alice prepares her grant proposal to the National Geographic Society’s Committee on Research and Exploration.

Within the year, she, her graduate student, Alline Storni, and I are stuck in remote cloud forest, abandoned by our helicopter pilot. We have noodles, tea, and trail bars for another two days and no idea what is the best path, if any, to take us out. Any path has to be one we cut ourselves.

The rainforests along the Atlantic coast of Brazil team with species found nowhere else on Earth. Some 8000 species of flowering plant, 200 species of birds and no one knows how many insects and fungi, are unique to these forests. Less than 6% of the forests remain.

This is the front line of conservation.

Maria Alice and her colleagues must provide Brazilian State and Federal agencies with the best possible advice to prevent extinctions. She is spending a sabbatical at Duke University, working with Clinton Jenkins, one of my research group.

Using satellite images, data on elevation, and a broad knowledge of where bird species occur, they’ll produce detailed predictions of where are the richest and most vulnerable parts of the Atlantic Forest.

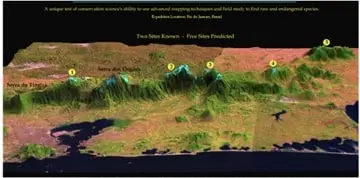

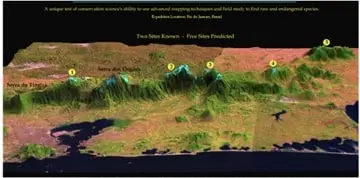

The computer predictions find that generally different species of birds have been collected where the computer thinks they should be and not where they shouldn’t. Maria Alice and Clinton point to the glaring exception. The grey-winged cotinga, discovered in 1980 by Michael Brooke, has been found on only two mountaintops. Along a hundred mile ridge of mountains inland of Rio de Janeiro, others areas of high elevation forest should also be home to this species.

There are no records — of this or any other species. Is the grey-winged cotinga more widespread — and so perhaps less threatened – than we thought? What other species occur here? What is happening to these forests? This is biological terra incognito — as exciting to us as those large blanks on the maps were to geographical explorers of the 19th century.

August 2003 and I’m in Rio for a brief visit. Unexpectedly, the State government provides a helicopter for a day. Its two pilots quiz Maria Alice about her work, then become enthusiastic supporters. They give their day to fly us along the mountain chain from Serra do Tinguá in the west to Desengano in the east.

It’s brilliantly sunny, with puffy white clouds for dramatic effect. We have a great day, with unrivalled views of the forests even if Alline does look a little green. Helicopter rides are particularly unnerving when the land falls away several thousand feet in a second as the helicopter crosses a ridgeline.

Three eastern mountaintops are visible from the city of Rio itself; Tinguá is the closest and so inaccessible that our pilots cannot find a place to land. They can at Araras, the next site, and east of Três Picos — three giant, sheer-sided pillars of granite rising several thousand feet from the forest below.

We work eastwards, preparing for the exploration that will begin in December — mid-summer in the southern hemisphere. We land, check the safety of each landing place, and record it to the nearest yard on our GPS. Unbroken forest stretches for miles, but we also see the encroachment of farms that reduce the forest to tiny fragments, ones we know will be too small to support many of the original, unique and likely unknown species.

Into the mountains…

Friday, December 5th, 2003. We lunch improbably in a luxurious home on the Fazenda Itatiba high in a valley a few miles from our intended camp. “It won’t be like this when we get to camp!” we joke with the fazenda’s administrator, Argélio.

The helicopter cannot carry everything we need in one trip, but will ferry the team and equipment in short trips between the fazenda and the camp. We’ve hired a private company this time. I just wish its pilot wasn’t wearing shiny black shoes, pressed black trousers and a white, starched shirt with epaulettes that vaguely suggest a naval uniform.

I fly on helicopter surveys across the world each year. Most pilots wear fatigues or tattered shorts, repudiate fashion, and have flight helmets that sport small insignia that hint of a previous life (“Da Nang”, for example) that one never brings up in conversation.

There’s a break in the clouds and I’m off. Knowing the risks, I ensure that my tent, pack, water bottle, and the remains of last night’s pizza are with me.

As we cross into the next valley, the clouds break. Over the landing spot, it’s bright sunshine. The pilot doesn’t land and circles around. I jab my finger energetically at the flat area of grass and smooth rocks on which we had landed in August.

As we land, I know from experience that he should keep the engine running, holding the helicopter under power in case it slips. He reduces power and I prepare to get out. He signals me to stay inside it. OK, I understand that rule: he wants to shut down completely.

Hell no, he then gets out. If wind tips the helicopter, the still rotating blades will hit the ground and the resulting shrapnel will turn me into hamburger. I get out, grab my gear and move well away from the helicopter. I notice I’ve a companion, a worker from the fazenda. In a minute, the pilot is off.

Fifteen minutes later, he’s back in our valley, but isn’t coming this way. He lands a mile or more below us in a depression. We wave. We strip off our shirts and wave them. Through the binoculars, I watch Alline and Maria Alice unload gear and the helicopter leaves. We will never see it again.

A silence descends. I slap on the sunscreen; I had the good sense to pack. My companion calls Maria Alice on our radio. “I told at the pilot it wasn’t the right place, but he said your site was not safe,” she tells me.”

So, why didn’t he then come to fetch us?” I ask. “I screamed at him that he had to. He ignored me and left.”

“Well,” I reply, “you have too much stuff to walk up to us, we’ll have to come to you.”

“Your companion is called Gilmar” Maria Alice tells me. He wasn’t expecting to stay and has nothing but the clothes he’s wearing. And he didn’t bring any food.

Between us, we can just manage to pick everything up. It takes us three hours to reach Maria Alice and Alline. By that time, the sun has turned to rain and we’re sodden. The route is partly a bog filled with tussock grass six feet tall. A few yards takes us five minutes — and another five to get our breath back. We head for a low forest, only to find it’s a tangled thicket of bushes and bamboo.

The only practical solution is to park the gear and cut a trail with the machete, then come back for the gear, and repeat the process. We’ll have to make “the hole” our camp and explore from there. It would take three trips to get to our planned destination with all our gear — at best, a long and exhausting day.

Maria Alice has already set up our mist nets. The nets catch small birds as they fly between the trees. My job is to listen for the grey-winged cotinga, to play a tape of its song to entice it to respond, and to record songs of birds we do not recognize.

We set up tents in the rain, glad we have a third for Gilmar. The final insult is the gas stove doesn’t work. As one attaches the burner, it’s supposed to puncture the canister through a rubber seal. It doesn’t. The prospect of cold food for two days sinks in. Out comes a pocketknife, we puncture the canister, and screw on the burner quickly before all the gas escapes.

Hot noodles taste so good in the field.

Saturday, December 6th starts cold and misty, then variously fogs, drizzles, sheets, spots, torrents, and all the other forms of rain for which we Britons have so many names. We band birds and listen for songs. Gilmar cuts a trail up the hillside to our north — the direction of “home,” the fazenda. “Just in case something goes wrong,” we tell ourselves.

What I hear on the trail is not encouraging. Scientists know almost nothing about the grey-winged cotinga. It’s supposed to live just below the tree line — just where we are. It’s the other fact worries me.

The bird is supposed to occupy forest at a higher elevation than its closest relative, the black and gold cotinga. The latter’s song is one of the extraordinary sounds of the Brazilian mountains — a pure whistle several seconds long, that rises mid—point to half a note higher. The altimeter says we should be too high for it. It’s so common here that the overlapping whistles create a continuous dissonance.

I return, soaked. As evening draws in, we’re all too cold to eat outside, so we eat inside my tent. Dinner is a protracted affair, hot noodles, soup, trail bars, nuts, chocolate, dry fruit, hot chocolate to drink. We’re all in our sleeping bags to keep warm, our wet clothes piled up around us.

Tomorrow night we’ll be warm again, back at fazenda in the next valley, where the owner’s generosity has extended to a night at his house.

Sunday, December 7th. I have never learned to love the sensation of getting out of a toasty, dry sleeping bag, and pulling on cold, damp rain gear, soaked socks and boots. It’s raining; I will be wetter yet within minutes. Only hard work will generate the body heat to warm the cold clothes.

By 1pm, we’re hearing our helicopter every 15 minutes, or at least think we are. None appears.

We have no radio and cell phone connections in the “hole”. Gilmar takes a radio and cell phone and heads up his rough trail. After an hour, from his perch above the forest, he can reach us by radio and the outside world by cell phone.

The pilot is still at home.

That means at least an hour to get to the helicopter in the Rio de Janeiro traffic, longer still to reach us. “I was expecting you to call me,” he tells us.

Maria Alice is furious, for we all know how clear her instructions had been and the impossibility of us calling him from where he left us.

Come in under the clouds and head up the valley from the southwest,” I ask Maria Alice to tell Gilmar to tell the pilot. The valley floor is still clear and the clouds above it are showing patches of blue sky. “If you can’t make it today, come first thing tomorrow.”

The pilot has abandoned us in a terrible place, one from which we cannot call the outside.

There’s no reason why he shouldn’t have been here. If he doesn’t arrive in the morning, it will be a disaster. Even if we can walk out, we’ll have to abandon all our gear and will be lucky to carry out our cameras and sound recording equipment. At some later date, we’ll need to come back by helicopter to recover it. This could delay the expedition for days, even weeks.

What do I tell National Geographic?

Maria Alice worries. It could be a lot worse: we have food.

Monday, December 8th morning. We pack for the hike out and by 9am are on our way. My tent is left up, with our gear packed as neatly as we can inside it. When we reclaim all that we must now leave, we want to be able to load it quickly. The rain has eased a bit.

The way out is simple and daunting. We know where we are and where we want to be — to the nearest yard from our GPS. It’s not far — a few miles — it’s just that there is a very large mountain in the way. We must go around it. Is to the left or the right better? Gilmar has told us the bad news: the forest has bamboo thickets, but above the tree line is worse. There are open areas, but they are bare granite on slopes too steep to climb.

We also know that the fazenda’s elevation is 1500 feet below our camp. Climbing up the mountain between us will be hard, but also mean that we’ll have to climb down those 1500 feet — plus every extra foot we climb up along the way.

Accidents are more likely going down than going up.

By lunchtime, we’re back in camp, wet, muddy from boots to hat, and smelling of rotten vegetation. After a thousand foot climb, we get radio and phone reception. We call the pilot, who incredibly thinks that we were going to call him to let him know when to come. He flew from Rio the previous afternoon, but gone to a town ten miles away and found it to be in the clouds.

That really angers us. We’ll get a bill for a thousand dollars for a trip that didn’t come close to us at a time when the weather was good in our valley.

We also reach Argélio at the fazenda by radio — and that’s the important news. He’s coming to find us and he’s not coming the short way. He’s coming up a different valley, though quite how and where is beyond me. Something about a tractor, I’m told.

Afternoon. Gilmar and I head up the opposite side of the valley from our trail. On the steep, but just accessible, granite slopes, we see a small cleft. It opens into a spectacular valley running southwards, that joins another, even larger valley coming in from the west. At its far end is the massive granite pillar of one of the Três Picos. Beyond this valley to the south, thick, white clouds cover the lowlands east of Rio de Janeiro.

Everything we can see is forest — surely one of the largest tracts of forest left in these mountains. This is a glorious, wonderful place to be stuck!

At the valley’s end — it looks miles away and thousands of feet below us — is a bright green spot. It’s a pasture and we see three men, tiny specks even through binoculars. Gilmar is talking to them on the radio. He takes off his shirt, puts it on a stick and waves it. I take off my blue rain jacked and do likewise. How on Earth they are going see us in the middle of this mountain beats me.

We wave vigorously and, improbably, they wave back.

Perched on the granite bluff, I spend the afternoon looking across it, listening. Abundant black and golds call. We’re above an exposed ridge, where the wind stunts the trees; this is supposed to be the grey-winged’s prime habitat. If it were here, I would hear it. Clouds fall into the valley, then are swept up into the sky, and from time to time brilliant sunshine turns misty grey greens into bright patches of green, with yellow and purple flowering trees adding highlights. By 5pm, our rescuers are in shouting distance in the valley below. At 730pm, just as it gets dark, six of them enter out camp.

Tuesday, December 9th. It blew hard last night, but there was little chance I would lose my tent — it had 7 men sleeping in it. Still, the wind snapped one of my tent’s poles and it’s oddly misshapen at first light.

There’s a trail bar and a cup of tea for everyone, one lump of sugar in each cup, except mine.

That exhausts all our food, but we’re happy. To run out of food before leaving, would have been inexcusably bad form. To leave our equipment behind would have been a disaster too: we just have enough helpers to carry it out.

It’s downhill all the way, sometimes steep, sometimes through dense bamboo thickets, but mostly through forest with a closed canopy that shades the forest floor and keeps it free of undergrowth.

Every step, I’m watch my feet, careful in where I place them, and use every handhold the trees and lianas afford. This is not the place to sprain an ankle.

An hour down, I see a bright orange frog on the ground.

It’s about the size of a dime and, as I admire it, others see another, then more. There’s a colony of about a dozen of them within a few yards. Bright and conspicuous, they are advertising that it’s not a good idea to touch them. When our companions do, we warn them not to touch their eyes or lips with their fingers.

“What are they?” we ask. “Does anyone know?” While we don’t, Maria Alice’s colleague at the university is a frog specialist, and we’ll ask him. We’ve done this before elsewhere and the answer has sometimes been that no one has seen the species before.

We descend past other frog colonies, down into the valley, below where we black and gold cotingas whistle. Soon, we’re hearing bellbirds — crow—sized, white cotingas that sound like cracked bells. There are more of them than any place I’ve ever been. Their hearing so many rivals works them up into a calling frenzy.

The canopy is now far above our heads, the going more open, flatter. We come to a real trail. For the first time in days, we can stride along, rather than tentatively place each foot down. I feel warm. My clothes are drying. Three hours after we started, we’re in the open pasture we saw yesterday, looking back to where we’ve come, marveling that anyone could see us from this distance.

We hike along another trail, find another clearing, hike more, and then in the next clearing there’s a tractor. How many people can you fit on a tractor? Ten — and their equipment — is the impossible answer.

On the back of a tractor, down a narrow trail a 4×4 would not navigate, past, then around the granite domes of Três Picos, not fast, not elegant, but down and down, warmer and drier with each slow, bumpy mile until we make it out. We walk stiffly the last few yards to the hot showers.

On the beach at Ipanema.

By 7pm, we’re on the beach at Ipanema, having a beer with Michael Brooke and discussing our plans. We should be in Arraras by now, but Maria Alice will need a day to regroup, check the equipment, buy food, and most important of all, find another helicopter pilot.

I will now miss Araras, for I must leave on Friday night. My body demands I spend tomorrow soaking in a hot bath and drying my gear. Michael arrived two days ago and hasn’t come this far to watch the beach. We set our alarms for 5am.

Wednesday, December 10th. By 830am, Michael and I are slogging up a trail in Serra dos Órgãos National Park heading for where he found the grey-winged cotinga 20 years ago. It’s my only hope to see the bird now and, importantly, to see how the forest here differs from that near Três Picos. Every muscle hurts as we climb hour after hour, stopping only for me to catch my breath.

We climb up through where the black and gold cotingas are whistling, then leave them below us. We listen, straining to hear the grey-winged’s call. No such luck.

Thursday, December 11th. There’s so much excitement in Maria Alice’s apartment as we pack the food, organize and check the equipment. In an instant, they’re off, and I’m alone. I wash my gear, write my notes, check my e-mail, enjoy a beer on the beach, listen to the BBC World Service after dinner.

I wasn’t expecting a phone call. From high on the ridge at Araras, exactly where they should be, exactly where I should be, Maria Alice has excellent reception. “Wish you were!” Next morning, the phone rings again.

We have grey-winged cotingas calling all around us” she tells me. You really should be there!”

“Yes,” I think, “I really should be.”

Postscript

Maria Alice completed the work for her National Geographic Grant. It would have been impossible if she had lost all the equipment. In time, she published her work as two scientific papers:

Alves, M. A. S., S. L. Pimm, A. Storni, M. A. Raposo, M. de L. Brooke, G. Harris, A. Foster, and C. N. Jenkins. 2008. Mapping and exploring the distribution of a threatened bird, Grey-winged Cotinga. Oryx. 42, 562-566

Alves, M.A. S., C.N. Jenkins, S.L. Pimm, A. Storni, M.A. Raposo, M. de L. Brooke, G. Harris and A. Foster. 2009. Birds, Montane forest, State of Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil. Check List 5: 289-200.

On the flight in August, we had seen one possible site where we could drive up a road to see the bird. Andy Foster explored that area and found it there.

Two years after I wrote this story, I went to that site, found the bird and filmed and photographed it for the first time.