The coming decade is likely to see species extinctions happening at 1,000 times the natural rate. The increasing appetite of a world population on pace to reach 8 billion is devouring our natural resources. In the face of relentless demand for timber, energy, minerals, and infrastructure, the unmitigated corruption of the planet’s natural resources goes largely unabated. The spiral of deforestation, climate change, and mass extinctions is accelerating.

To protect all life on Earth, including our own species, biodiversity scholar E. O. Wilson has called for ecosystems preservation on the scale of “Half Earth.” But which half? And How? We’d like to talk about that.

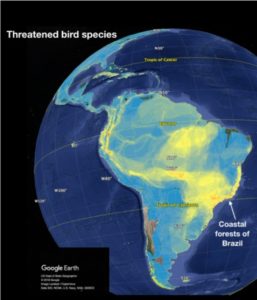

Many of the world’s species live in an area smaller than 1,000 square kilometers (the world’s land area is about 149 million square kilometers). For these species, an infinitesimal share of the planet is their entire world. When it’s gone, they are too. We know how to prevent that. And with our partners, we are making progress.

Creating habitat corridors, setting aside small critical areas for conservation, is now a proven approach for practical actions that have big impact.

Geography is Destiny

The variety of life on earth is not spread evenly, but is concentrated in very special places. More than 60% of earth’s terrestrial species are confined to only 1.4% of the Earth’s land surface

1.

For about ninety percent of threatened species, habitat destruction is the main threat to survial

2. Overwhelmingly, it’s these species with small geographical ranges, taking up very little space on the planet, that are the most vulnerable to extinction.

Other things being equal, habitat destruction is more likely to exterminate a species that lives on a mountaintop, island, or forest fragment than one that inhabits large expansive areas. Small-range species simply have nowhere else to go.

Why It Matters

With an understanding of the risks posed by fragmented ecosystems, we can begin to understand what’s going wrong and how to address it.

Satellite images show that generally within the mostly tropical concentrations of threatened species, human actions destroy or damage habitats, leaving behind only small, isolated fragments. These patches may be too small to sustain viable populations. For a variety of reasons, we have disproportionately harmed those places where small-ranged species are concentrated.

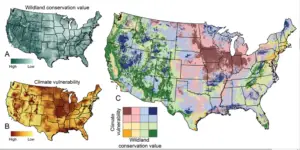

Unfortunately,funding for conservation is not enough to assist all species under threat. Therefore, it’s important to find a way to save the most species at the lowest cost. Simply put, the key to success is leverage – focusing on the right places and finding where to get the highest impact from every conservation dollar.

Habitat corridors provide one of the highest returns on investment for biodiversity conservation worldwide. One can create landscapes that massively slow the loss of species through the connection, protection, and restoration of key corridors without having to purchase large areas.

How To Save the Most Species

A good starting point is to target areas where high concentrations of small range species live in extremely fragmented landscapes. The environmentalist Norman Myers coined the term “biodiversity hotspots” for these places where concentrations of small-ranged species have collided with extensive habitat loss. His influential insight was the starting point for actionable science.

The team at Saving Nature extends this concept to practical actions, mapping where small-range species are concentrated, modeling their habitat loss, and looking for a base to rebuild from surviving remnants. We look for the convergence of species density, broken linkages between forests, and the opportunity to purchase private land.

Scientists have a prescription for how to slow the rate of extinction. Very roughly, a forest fragment must be at least 1,000 hectares to slow the time it takes to lose half the species to a century or more. By creating corridors that we reconnect the habitat fragments and making them large enough, species will have a fighting chance to persist in the long term.

Saving Nature’s planning models use big sets of data to produce strategic maps where to best intervene. Rather than focusing on a few charismatic species, we maximize conservation impact by directing and leveraging efforts towards places facing imminent loss of biodiversity and destruction of unique ecosystems. Like assembling missing puzzle pieces, we look for the best place to reconnect isolated remnants. Their ultimate goal is to create larger connected areas by reforesting small habitat corridors to reunite isolated populations that have become genetically stranded.

For over a decade, the team at Saving Nature has worked with local partners to create habitat corridors in some of the hottest of biodiversity hotspots in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, India, and the Indonesian island of Sumatra. All areas high in biodiversity and endemism. All areas that have lost a great deal of their once expansive forests. Our results can be seen from space, in before and after satellite imagery the team monitors annually.

The Backstory — How Much Can We Save?

Surprisingly, we don’t need as much land as you would think to save species from extinction. Here are some key facts and figures to frame the challenges and opportunities:

- There are 300,000 plant species and 27,296 vertebrate species on earth.

- There are 133,149 plant species and 9,645 vertebrate species are endemic to only one geographic region.

- The top five biodiversity hotspots for vertebrates are home to about 43% of all vertebrate species and 39% of all plant species:

-

- The Tropical Andes (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela) tops the list for biodiversity with a total of 48,389 species of plants and vertebrates. It harbors 12.4% of the world’s vertebrate species (3,389 species) and 15% of the world’s plant species (45,000 species). This region is also home to more endemic vertebrates and plants than anyplace else on earth, with 1,567 endemic vertebrates and 20,000 endemic plants.

- Mesoamerica (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Central and Southern Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama) has 26,859 total species. It is home to the second highest diversity of vertebrate species, with 10.5% of the world’s total (2,859 species), of which 1,159 exist nowhere else on earth. It ranks fourth in plants, with 8% of the world’s total (24,000 species), of which 5,000 are endemic plant species.

- Indo-Burma (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, and portions of eastern India and southern China) has a total of 15,685 species. This region has the third highest vertebrate diversity with 2,185 species (8% of the world’s total), of which 528 are endemic to the region. It is also home to 4.5% of the world’s plants (13,500 species), of which 7,000 are endemics.

- Sundaland (Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and surrounding islands) has a total of 26,800 species. It ranks fourth in terms of vertebrates, with 6.6% of the world’s total (1,800 species), of which 701 are unique to the region. This lush region is second in terms of plants with 8.3% of the world’s total (25,000 species), of which 15,000 exist nowhere else on earth.

- Western Ecuador Choco/Darien rounds out the list with 10.625 total species. Here you’ll find 5.9% of the world’s vertebrate species (1,625 species), of which 418 are endemic to the region. There are 9,000 species of plants (3% of the world’s total), of which 2,250 are endemic.

We have installed a network of camera traps throughout our wildlife corridor to record the species moving through on a 24/7 basis.

We have installed a network of camera traps throughout our wildlife corridor to record the species moving through on a 24/7 basis.