The World’s Great Forests You’ve Never Heard Of

February 5, 2020

Andrew Schiffer takes a global tour of the world’s greatest forests and makes the case for taking “remote ownership” of their protection. His call to action encourages people to learn more about the world around us and get involved in saving these special places.

The World's Great Forests You've Never Heard Of

by Andrew Schiffer

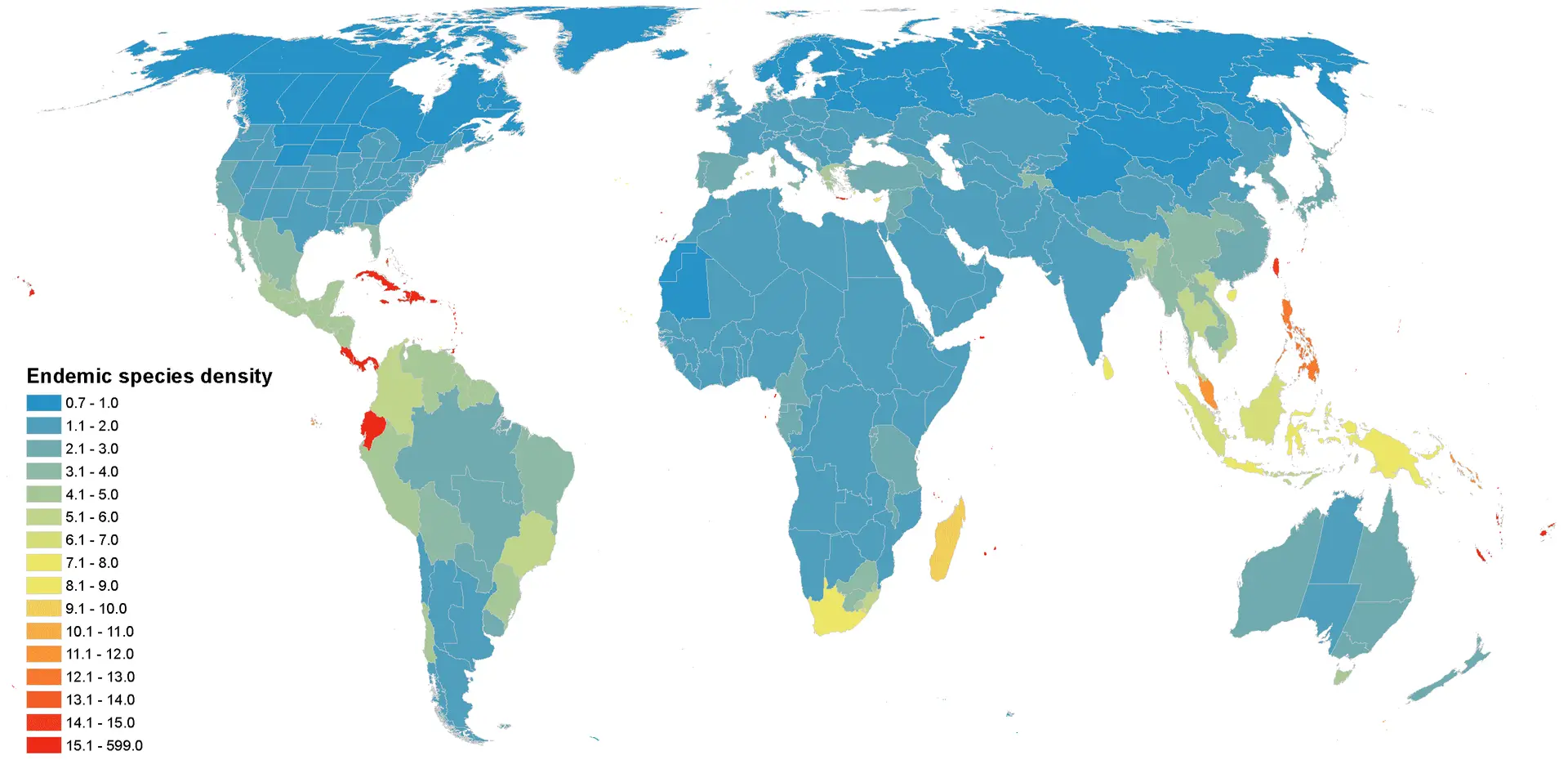

With limited funding and climate change upon us, conservationists must decide which forests to focus on and preserve. Although every forest possesses its own value, in order to prioritize funding, it is critical for our humanity to identify ‘biodiversity hotspots’ where the highest concentrations of endemic species are facing the largest loss of habitat.

I have narrowed down the candidates to five particularly vital hotspots: Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, Choc/Darien/Western Ecuador, Western Ghats/Sri Lanka, Indo-Burma, and the Tropical Andes.

These hot spots all contain a treasure trove of critical, different wildlife and plant species. In addition, many of them are brimming with life endemic only to the area. In learning more about these crucial hotspots, specifically about the statistical number of species that inhabits each area, we will learn some important facts that are compelling for each of us to take “remote ownership” and learn more.

These numbers are more shocking when “In contrast, the United States and Canada, with an expanse 8.8 times larger than the 25 hotspots combined, have only two endemic families of plants.” Although we are providing a brief overview of the importance of conserving each forest, there is still a lot to learn and we encourage you to explore the Saving Nature website to learn more and hopefully be inspired to carry out some research on your own!

South America

First off, Brazil’s Atlantic Forest makes up such a huge amount of the Earth’s surface that it contains two of the world’s largest cities: Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. The forest spans over 3,000 km along the coast of Brazil and into Paraguay and Argentina. The forest is home to the biggest big cat in South America, the jaguar, as well as two indigenous tribes: The Tupi and the Guarani. In 1832, Charles Darwin explored the forest during his expedition on the Beagle. The forest is also home to over 2% of both the world’s endemic plants and vertebrates. It boasts the third largest number of endemic plants in the world, topping 8,000. However, in the face of growing threats, the forest has recently lost all, but 7.5% of its original primary vegetation and species, threatening the very existence of the native Jaguar.

The Tropical Andes, also located in South America, stands as an equally special woodland. Holding over 20,000 endemic plants as of yet discovered; the forest has long fascinated scientists. 1,666 bird species call it their home, a number that far exceeds any other hotspot in the world. Furthermore, the Tropical Andes contains at least 2% of the total endemic plants and vertebrates worldwide. With jaw-dropping statistics such as this, as well as 6.7% of all plant species extinct, we must give it our utmost attention.

Rounding out the South America candidates, the Choco/Darien/Western Ecuador forest presents its own case for being saved, struggling to maintain the mere 4.9% of its primary vegetation that remains. Due to its isolation, the forest is particularly attractive to endemic life. This stems from the forests on the western side of the Andes having evolved entirely differently from their counterparts on the eastern side.

The numbers are quite staggering: 830 birds (85 endemic), 235 mammals (60 endemic), 210 reptiles (63 endemic), and 350 amphibian species (210 endemic). Without question, the forests are one of the primary sources of endemic life. They also contain 0.8% of the global total of endemic plants and 1.5% of the world total endemic vertebrates.

They run along the entire Columbian coast and are made up of mountains, rain forests, and coastal areas. Species include jaguars, ocelots, giant anteaters, tapirs, and tamarins. The adorable cotton-top tamarin can only be found there and could risk extinction without our immediate intervention. Such profound data compel us to consider the Choco/Darien/Western Ecuador Forest’s significance.

Tropical Asia

As we travel to the 2 million km of tropical Asia and the lowlands of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, we find the Indo-Burma forests. With 1,170 bird species, 329 mammal species, 202 amphibian species, and 484 reptile species, these forests contain many of the world’s great animals: leaf deer, kouprey, white-eared night-herons, Mekong giant catfish, and Jullien’s golden carps to name but a few.

Nearby stretches the last of the five highlighted forests: the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka forests. The Western Ghats region of India contains more than 30% of all plant, fish, herpetofauna, bird and mammal species found in the country, yet account for less than 6% of the national land area. Once again the numbers are staggering: 528 bird species (40 endemic), 140 mammal species (38 endemic), 259 reptile species (161 endemic), 146 amphibian species (116 endemic). Species include the mountain shrew, the slender loris, the grizzled squirrel, Layard’s striped squirrel, 144 aquatic birds, the black-spined toad, the skittering frog, the Indian bullfrog, and the Malabar torrent toad.

Furthermore, these forests are home to 0.7% of the world’s endemic plant species. In 200 square kilometers, you’ll find an average of 35 species of plants found nowhere else on earth. You’ll also find 1.3% of the world’s endemic vertebrates – that’s an average of almost 6 species found only here. With only 6.8% of its primary vegetation remaining, the Western Ghats/Sri Lanka forests call out for our help.

Caring for Our Great Forests

If we do not help save these one of a kind, crucial, magical places, the world will face mass extinction, causing millions of species to die out. This will cause an alarming imbalance in our ecosystem and cause unforeseen damage to our ecosystem and our daily life as humans. While we may feel comfortably safe here now, and these magical forests may feel far away, still there is a crucial role each of us can play in saving our magical, treasured species, and in saving nature. Feel proud and be a part of this vanishing opportunity—do not stand idly by! Thankfully, and excitedly, together we can all play a critical role in saving nature. YOU HAVE MADE A GREAT FIRST START IN LEARNING MORE.

Although they are far away for many of us, these forests contain some of the most important endemic species and vegetation in the world. We need to answer the call! It is time to come together as one and explore ways to support conservation efforts. It is daunting to take on the task of conserving the world. Common questions are likely to come up: How do we get started? What are the most important places? How could my effort even make a difference? Very little information is provided to us directly about actual concrete ways to make real, effective change. It can be difficult to know how to make a real difference and ensure that your hard work will be effective. Well, not only can you make a difference, but we can help you get started today.

There are many great organizations out there. One that is particularly relevant is Saving Nature because, coincidentally, it is focused on saving the very same forests we just talked about. Go for a life-saving adventure and explore their projects. Together, we can save our planet, one forest at a time. Together, we can help zero in on helping save the most important hotspots in the world and make real, lasting beautiful change. Do not stand idly by—you can make yourself and our planet earth proud! Along with your other great qualities, you are now a proud nature-saver! If we do not act now, there will not be enough time to save these magical, critical species and our planet. Please kindly act now and help Saving Nature. Grateful for you, nature-saver!

help save the world's great forests

Saving Nature works in biodiversity hotspots around the world to prevent extinctions and fight climate change. Guided by science, using annual surveys with drones and camera traps, we show donors where the forests and species are returning.